Introduction

A 16S LFP battery charges at 50A when one cell hits 3.62V, approaching the 3.65V damage threshold. The BMS detects this immediately and drops the Charge Voltage Limit (CVL) from 56.0V to 55.2V, signaling the inverter to stop. Four seconds later, current finally drops to zero.

In those four seconds at 50A, approximately 55-watt hours were forced into a pack actively rejecting charge. That cell absorbed energy it could not safely handle. Repeat this daily for six months and you get measurable capacity loss from repeated micro damage during what should have been protected operation.

This is not a protocol failure. The CAN bus worked perfectly. Messages arrived intact. The problem is the gap between what the BMS transmits and what the inverter actually does with that information. Response timing, limit interpretation, and default behaviors create a space where batteries degrade while both devices report normal operation.

This guide covers the mechanisms behind these failures: the control loop timing that matters more than protocol choice, the physical layer issues causing 90% of field problems, the SOC drift making customers think their battery is dying, and the diagnostic approach separating configuration errors from actual hardware incompatibility.

How Communication Actually Fails

Most BMS inverter communication problems do not announce themselves with error messages or failed commissioning. They appear months later as capacity loss, nuisance trips, or cells drifting apart despite a working balancing system. The communication link reports healthy, protocol handshake succeeds, both manufacturers insist their device functions correctly while the battery degrades.

The Five Failure Patterns

1. Chronic Overcharge

Six months post installation, customer reports reduced runtime. Cell voltages sit at 3.62 to 3.65V at full charge instead of 3.50 to 3.55V. Capacity testing shows 10 to 15% loss on relatively new cells.

What happened: The inverter lost communication at some point and fell back to internal default charge voltage of 57.6V (3.60V per cell for 16S), higher than the BMS requested 56.0V CVL. The inverter never resynchronized with BMS limits after communication restored. It has been overcharging by 0.1V per cell every single day for months.

At LFP chemistry voltage curve, 0.1V is the difference between 3.45V (relaxed cells, minimal stress) and 3.55V (elevated voltage stress, accelerated SEI growth, calendar aging in overdrive). Daily overcharge at this margin appears as capacity fade that looks like premature aging but is accumulated damage from voltage abuse.

2. Nuisance Disconnect Cycling

System drops offline 2 to 3 times per week during charging. Inverter throws “Battery disconnect” or “Communication lost” faults. Customer hears contactor clicks before shutdown. After 30 to 120 seconds, system recovers and resumes charging. No pattern to time or charge level.

What happened: EMI from inverter switching power electronics couples into the CAN bus cable. During high power operation, noise corrupts CAN messages. The BMS watchdog timer expires after 10 seconds of failed communication, interprets this as critical fault, opens main contactors to protect cells.

Disconnection stops current flow, reducing inverter switching noise. CAN communication clears. BMS sees valid messages, closes contactors, charging resumes until the next EMI spike triggers the cycle again.

Contactors are not designed for repeated switching under load. Opening at 50 to 100A causes arcing across contacts. Each arc erodes contact material. After 20 to 30 cycles, increased contact resistance appears. After 50 to 100 cycles, contacts can weld partially or develop unreliable connection.

3. Balancing That Never Happens

Initial commissioning shows 50mV cell voltage spread. After one month, 80mV. After three months, 120mV. After six months, 180 to 200mV. Customer complains usable capacity is shrinking; system shuts down early with 20 to 30% SOC still showing.

What happened: BMS balancing threshold is 3.48V per cell. Inverter CVL is configured to 3.45V per cell (54.4V for 16S) for longevity. Cells never reach 3.48V because charging stops at 3.45V. Balancing never activates.

Also Read: Why Passive Balancing BMS Fails in High-Discharge Solar Battery Systems

Or The BMS correctly requests 2A charge current during final top balance when cells are between 3.48 to 3.50V. The inverter has a 5A minimum charge current floor. It ignores the 2A request and delivers 5A anyway. Voltage rises too quickly through the balancing window. Balancing resistors lack time to equalize cells before voltage hits CVL and charging terminates.

Cells drift 10 to 20mV apart per month from small differences in self discharge rate and internal resistance. Without balancing correction, this accumulates. After six months, the weakest cell limits pack discharge while stronger cells retain 20 to 30% capacity. System appears to have lost capacity but is actually just imbalanced.

4. SOC Drift and Premature Cutoff

Customer reports battery dies early. Inverter display shows 20 to 25% SOC remaining but system shuts down unexpectedly. Or opposite: inverter shows 100% SOC but charging continues another 30 to 45 minutes before terminating.

BMS display shows different SOC than inverter display. Gap grows over time from 2 to 3% difference to 10 to 15% after weeks.

What happened: Both BMS and inverter calculate SOC independently using coulomb counting (integrating current over time). Current sensors are typically accurate to ±1%. Over 100 kWh throughput, that is ±1 kWh accumulated error. For a 10 kWh battery, that is 10% SOC drift.

The BMS recalibrates SOC when cells reach balancing voltage (its definition of 100% full). The inverter recalibrates based on rested voltage and a lookup table. They recalibrate at different times using different criteria and drift apart again immediately.

When inverter thinks SOC is 20% but BMS knows it is actually 5%, the BMS emergency disconnects to protect cells from over discharge. From the customer perspective, battery died with 20% left.

5. The Compatibility Discovery Timeline

New installation. Battery and inverter both claim Pylontech compatibility. Bench test with short cables works; communication establishes, CVL and CCL values look correct. Install on site with 4 meter cable run. Commission: communication established, no errors.

Two weeks later, customer reports overnight shutdown. Logs show “Communication timeout” at 2:37 AM. BMS logs show valid messages sent continuously. Inverter logs show it stopped receiving messages at 2:37 AM for 43 seconds, then resumed. Next week, happens again. Then twice in three days. Then daily. Both manufacturers insist their device works correctly.

What happened: Proprietary protocol nightmare. Devices use similar but not identical Pylontech implementations. Subtle timing differences, message interpretation variations, or firmware version incompatibilities create edge cases that do not appear during brief testing but fail under sustained operation or specific conditions.

The short bench test cable worked because signal integrity was perfect. The 4 meter field installation introduces enough capacitance and inductance that marginal timing margins now cause intermittent failures. Or firmware versions installed were never tested together.

Quick Physical Diagnostics

Before analyzing protocol timing or firmware versions, check these physical layer issues causing 90% of communication problems:

Termination resistance:

Power off both devices. Disconnect CAN cable from one device. Measure resistance between CAN H and CAN L. Should read 60Ω (two 120Ω termination resistors in parallel). If 120Ω: one termination missing. If 40Ω: three terminations instead of two. If open circuit: no termination.

Cable quality versus EMI environment:

Unshielded CAN cable parallel to DC bus for more than a few centimeters invites noise coupling. Quick test: does communication problem correlate with power level? If failures only happen during high rate charging above 50A or discharge, suspect EMI coupling.

Configuration verification:

Inverter protocol setting must match BMS protocol type exactly. Baud rate must match on both devices (500 kbps standard). DIP switches on BMS must match manual positions. CAN IDs must be unique if multiple batteries.

These take 10 minutes to verify and solve the majority of communication problems without protocol analysis.

Inverter Battery Communication Protocols

The BMS inverter conversation is not just status reporting. It is a real time control loop where the BMS calculates safe operating limits every second and the inverter enforces them immediately. When this loop works, cells stay within safe voltage and current boundaries. When it breaks, you get the failure patterns from Section II.

What Gets Transmitted Every Second

Charge Voltage Limit (CVL):

Maximum pack voltage the inverter should apply. For a 16S LFP pack, this is not static. Early in charge cycle at 3.30V per cell, CVL might be 56.0V (3.50V average per cell). As highest cell approaches 3.55V, CVL drops to 55.2V (3.45V average). If one cell hits 3.60V due to imbalance, CVL might drop to 54.4V (3.40V average) to halt current immediately.

The BMS protects the weakest link, the highest voltage cell, by controlling pack level voltage. This only works if the inverter responds immediately.

Charge Current Limit (CCL):

Maximum charge current the battery accepts right now. Changes based on cell voltage, temperature, cell voltage spread, and SOC. At 3.30V per cell, might allow 100A. At 3.50V, drops to 20A. At 3.55V, drops to 5A or less. A properly implemented BMS recalculates CCL every second based on real time cell conditions.

Discharge Current Limit (DCL):

Maximum discharge current allowed. Similar dependencies on cell voltage, temperature, and cell imbalance.

State of Charge (SOC):

BMS estimate of remaining capacity, 0 to 100%. Calculated via coulomb counting with periodic voltage based recalibration. This is estimated, not measured, and accuracy degrades between recalibration events.

Status and alarm flags:

Hierarchical warnings and faults. Warnings should trigger inverter response. Alarms often mean BMS is about to disconnect, giving inverter brief window to ramp down gracefully.

The CVL Protection Mechanism Failure

For LFP cells, sustained voltage above 3.65V per cell accelerates SEI layer growth, reduces cycle life. Safe charging voltage is typically 3.50 to 3.55V per cell for cycling.

Also read: Why Float Charging Lithium Batteries Is Unnecessary and Harmful

In a balanced pack, BMS sends CVL of 56.0V (3.50V x16 cells). Inverter charges at constant current until pack voltage reaches 56.0V, then switches to constant voltage mode, holding 56.0V while current tapers naturally.

Read About the stages of lithium charging and the mistakes usually made: 5 Critical Truths About Absorption Stage in Lithium Batteries and What’s Really Happening During Bulk Charging in Lithium Battery

With cell imbalance, one cell (Cell 9) reaches 3.55V while others are at 3.45V. Pack voltage is 55.4V (average 3.46V), but Cell 9 approaches its limit. BMS detects Cell 9 at 3.55V and recalculates CVL to 55.2V. BMS transmits new CVL in next message (within 1 second). The inverter should immediately reduce charge voltage from 55.4V to 55.2V, stopping current flow and preventing Cell 9 from going higher.

The response time gap:

This is where protection fails in real systems.I have measured inverters taking 3 to 5 seconds to respond to CVL change. During those 3 to 5 seconds at 50A charge current, 30 to 75 watt hours minimum get pushed into the pack. If Cell 9 was at 3.55V when BMS sent the limit, and we push another 40Wh into the pack with current flowing preferentially into Cell 9, that cell might reach 3.60 to 3.62V before current actually stops.

The BMS tried to protect at 3.55V. The inverter response lag meant protection activated at 3.60V or higher. Do this daily and you accumulate damage the BMS was designed to prevent.

Inverter behaviors making it worse:

Some inverters average CVL over 3 to 5 messages to filter noise or transient spikes. Emergency limit reductions get delayed by design. The BMS screaming “STOP NOW” gets interpreted as “maybe consider slowing down over the next few seconds.”

Some inverters implement maximum voltage change rates of 0.1V per second regardless of CVL. BMS sends CVL drop from 56.0V to 55.2V (0.8V change). Inverter ramp limiter allows only 0.1V per second, taking 8 seconds to reach new setpoint. During those 8 seconds, charging continues at nearly full voltage into cells the BMS wanted protected immediately.

This is system stability versus cell protection. The inverter optimizes for one, the BMS for the other, and they work against each other.

CCL and DCL: Current Limits That Get Ignored

Current limits should be as dynamic and critical as voltage limits. In practice, they get treated as advisory suggestions.

Also read: CVL, CCL, and DCL: Understanding Dynamic Battery Limits in Real-Time

The current controller time constant problem: Most inverters use PI controllers for current regulation with time constants of 1 to 2 seconds. When BMS sends emergency DCL reduction from 80A to 0A, inverter current controller begins ramping down. At T equals 1 second, current dropped to 40A. At T equals 2 seconds, current dropped to 10A. At T equals 3 seconds, current reaches 0A.

During those 2 to 3 seconds, approximately 120 to 180 watt hours were extracted from a cell already at damage threshold. The BMS sent DCL equals 0A immediately. The inverter control loop physics meant current continued for 2 to 3 seconds anyway. The protection was theoretically in place but practically ineffective.

Minimum current floor issues: Many inverters have minimum operating currents of 2 to 5A for charge. BMS requests 0.5A charge current for slow top balance at 3.48V. Inverter minimum is 5A. Inverter delivers 5A regardless of BMS request. Cell voltage rises 10 times faster than BMS expected. Balancing window (3.48 to 3.50V) is passed in 8 minutes instead of the 60 plus minutes needed for resistive balancing to equalize cells. Balancing completes maybe 30% of required work. Cells remain imbalanced.

The BMS calculated exactly what current it needed. The inverter could not physically deliver it. Communication worked perfectly; the hardware did not support the control strategy.

Reader takeaway: CVL/CCL/DCL aren't just three numbers, they're a real-time control loop. Loop timing and response matter more than protocol choice.

Protocol Reality

The communication protocol is rarely the problem. CAN bus is mature and robust. When communication fails in solar storage systems, it is almost always physical implementation, configuration errors, or subtle differences between compatible protocol interpretations.

CAN Bus Physical Layer

CAN dominates residential solar storage because it was developed for automotive applications where multiple electronic control units communicate reliably in electrically noisy environments. It provides multi drop capability, differential signaling for noise immunity, built in error detection, and defined collision handling.

Termination:

CAN bus is a transmission line at 500 kbps frequencies. Unterminated transmission lines create signal reflections. Correct termination is 120Ω resistor at each physical end of the bus. With two resistors, you measure 60Ω between CAN H and CAN L.

What you find in the field: no termination (cable has no resistors, signals reflect creating ringing), single termination (one end has 120Ω, other has nothing, still creates reflections), triple termination (someone added resistor to be sure, you measure 40Ω, overloads CAN transceivers).

Also Read CAN Bus Physical Layer: The 60-Second Fix for Battery Communication Failures

Cable quality and length limits:

CAN specification for 500 kbps allows 100 meters in ideal conditions. Reality in solar inverter installations with high frequency switching noise, high DC currents creating magnetic fields, and cables running parallel to DC bus: unshielded twisted pair in low EMI environment works 5 to 10 meters reliably. Unshielded in high EMI environment works 2 to 3 meters. Any cable run over 10 meters should drop to 250 kbps or lower baud rate.

Ground loops and common mode noise:

If CAN GND is connected at both battery and inverter ends, potential difference between these grounds (several hundred millivolts during high current flow) drives current through the CAN ground conductor. This common mode current induces voltage in CAN H and CAN L conductors, corrupting the differential signal. Symptom: communication works fine at low power, fails during high current charge or discharge when ground potential difference is highest.

Pylontech Protocol

Pylontech published their CAN protocol for inverter integration. It became the de facto standard because many inverter manufacturers added Pylontech compatibility and many battery manufacturers cloned the protocol to gain access to those inverters.

The message structure uses CAN 2.0B extended frames at 500 kbps. Message 0x351 contains CVL, CCL, DCL, and discharge voltage limit. Message 0x355 contains SOC and SOH. Message 0x356 contains pack voltage, current, and temperature. Message 0x359 contains alarm and warning flags.

Also Read: Pylontech Protocol In Inverter Battery Communication.

Where clone implementations diverge:

Timing assumptions vary. Original Pylontech sends messages at exactly 1000ms intervals. Clone A sends at 800 to 1200ms intervals (jitter from poor timer). Clone B sends in bursts (three messages rapidly, then 1.5 second gap). Inverter written for original timing might timeout when messages arrive irregularly.

Byte order varies. Most use little endian (least significant byte first), some clones use big endian. CVL value of 56.0V sent as 560 (0x0230) appears as either byte 0 equals 0x30, byte 1 equals 0x02 (little endian) or byte 0 equals 0x02, byte 1 equals 0x30 (big endian). If inverter expects one and gets the other, CVL interpreted as 5.60V or 12,288V.

Scaling factors vary. Spec says 0.1V units. Some implementations use 0.01V units (10 times higher resolution). Inverter interprets 560 as 56.0V when BMS meant 5.60V, resulting in massive overcharge.

None of this is documented. You discover it by capturing CAN traffic with analyzer and comparing byte by byte against known good implementations.

Proprietary Protocols

Proprietary protocols have message structures that are not published, often encrypted or obfuscated. With Pylontech protocol, if communication fails, you can connect CAN analyzer, capture traffic, decode messages, see what BMS is sending, verify inverter is receiving, identify where interpretation fails.

With proprietary protocol, CAN analyzer shows hex data meaningless without the decode key. No published message structure. Cannot verify if BMS is sending correct values. Cannot verify if inverter is interpreting correctly. Both devices might be working perfectly to their own specifications while being incompatible with each other. You are completely dependent on manufacturer support.

Also Read: Proprietary vs Open Battery Protocols

Reader takeaway: Physical layer and implementation matter more than protocol choice. Proprietary isn't just vendor lock-in, it's a diagnostic dead-end.

SOC Calculation: Why BMS and Inverter Disagree

State of Charge is not measured; it is estimated. Both BMS and inverter calculate SOC independently using imperfect methods, and over time their estimates diverge.

Also Read: SOC Drift in Lithium Battery Systems: Why Your BMS and Inverter Disagree

Customer loads battery in evening. Inverter display shows 22% SOC. System suddenly shuts down with “Battery disconnected” error. Customer calls: “Battery died with 22% remaining.”

What happened: BMS calculated SOC reached 5% (its cutoff threshold). Minimum cell voltage hit 2.80V (under voltage protection threshold). BMS opened contactors to protect cells. Inverter was still showing 22% because its SOC calculation drifted 17% higher than BMS. From customer perspective: lost 17% of battery capacity for no reason.

Or opposite scenario: Inverter display shows 100% SOC. Charging continues for another 45 minutes. Customer confused: “Why is it still charging if it is full?” What happened: Inverter SOC calculation reached 100% based on its coulomb counting. BMS SOC was actually at 87% (13% drift). BMS has not reached balancing voltage yet, continues requesting charge current. Charging continues until BMS reaches its definition of full (all cells at 3.50V).

Recalibration Requirements

Coulomb counting drift is inevitable. The solution is periodic recalibration, resetting SOC to known value when battery reaches defined state.

Full calibration point: All cells at balancing voltage (3.48 to 3.50V for LFP), current near zero for 10 plus minutes. When this condition is met, cell voltage proves cells are actually full, zero current proves no charging or load activity (voltage has stabilized), BMS resets SOC calculation to 100%.

What prevents recalibration in real systems:

Common configuration: BMS balancing activates at 3.48V per cell. Inverter CVL set to 3.45V per cell (54.4V for 16S) for longevity. Charging terminates when pack voltage reaches 54.4V. At this voltage, cells are at roughly 3.40V average, highest around 3.43V. Balancing voltage (3.48V) never reached. BMS never sees the full condition. SOC recalibration never happens. Drift continues indefinitely.

Another issue: Full requires current near zero for 10 plus minutes. Many inverters have minimum charge current floors (2 to 5A) and continue drawing this even when batteries are full for inverter self consumption and parasitic loads. If current never drops below 3A, BMS waiting for current less than 1A for 10 minutes never sees this condition. Recalibration does not trigger.

Balancing Communication Dependencies

Cell balancing is critical for long term performance. Without it, manufacturing tolerances and self discharge variations cause cells to drift apart, reducing usable capacity over time. Balancing requires specific voltage and current conditions that must be coordinated between BMS and inverter through communication.

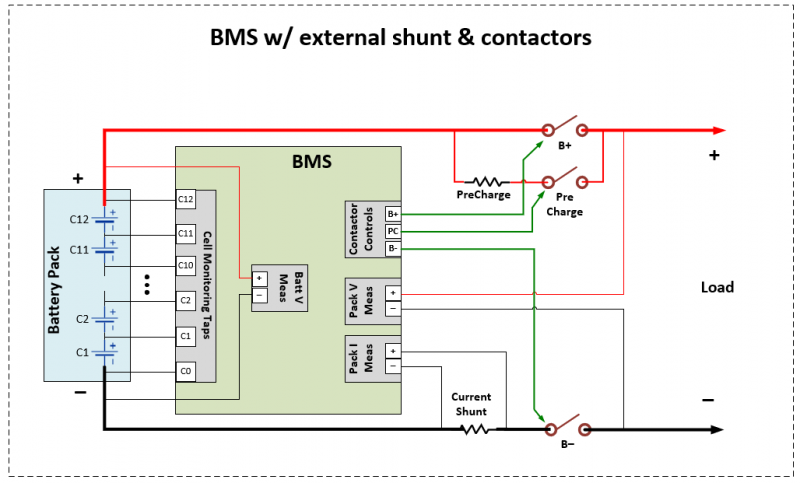

Passive Balancing: The Timing Window Problem

Each cell has a small resistor (50 to 100Ω, 1 to 2W) and a MOSFET switch controlled by the BMS. When cell voltage exceeds balancing threshold, BMS closes that cell switch, connecting resistor across cell. Current flows through resistor, dissipating energy as heat, slowly draining that cell voltage down to match others. Typical balancing current is 20 to 100mA per cell.

Read: Why Passive Balancing BMS Fails in High-Discharge Solar Battery Systems

For 280Ah cell at 3.50V (nearly full), 50mV represents roughly 0.2 to 0.5Ah charge difference. At 50mA drain rate, that is 4 to 10 hours to equalize. This is why balancing is slow.

BMS balancing threshold is typically 3.48V for LFP. Below 3.48V, balancing inactive. Above 3.48V, balancing active on cells exceeding threshold. For balancing to work, cells must reach balancing voltage, stay in balancing window (3.48 to 3.52V) long enough for resistors to equalize charge, and not rise so fast they exceed safe voltage before balancing completes.

If CVL is set to 56.0V (3.50V per cell), balancing window is 3.48V activation to 3.50V CVL termination, a 20 to 40mV range representing 10 to 30 minutes of slow charging time. If CVL is set to 54.4V (3.40V per cell), charging stops at 54.4V, cells never reach 3.48V balancing threshold, balancing never activates, imbalance accumulates indefinitely.

CCL Taper Requirement for Passive Balancing

Even if CVL is set correctly, balancing still fails if charge current is too high. At 100A charge current into 16S pack, pack voltage rises at roughly 0.05 to 0.1V per minute. Cells pass through balancing window (3.48 to 3.50V) in 2 to 5 minutes. Balancing current is 50mA per cell. Charge equalization possible in 2 to 5 minutes is 50mA times 2 to 5 minutes equals 1.6 to 4.2 mAh. This is nearly nothing. Cells might differ by 100 to 500mAh due to imbalance.

At high charge current, cells blow through balancing window before balancing can accomplish anything meaningful.

Proper BMS behavior during top balance: as pack approaches full (cells reaching 3.45V), BMS should reduce CCL progressively. At 3.46V, CCL drops to 20A. At 3.47V, CCL drops to 10A. At 3.48V, CCL drops to 2A. At 3.49V, CCL drops to 0.5A or requests zero current, holding voltage constant.

At 0.5 to 2A charge current, voltage rises very slowly. Cells spend 20 to 60 minutes in balancing window. Balancing current of 50mA per cell over 30 minutes equals 1,500 mAh equals 1.5Ah. For cells with 50 to 200mAh initial imbalance, 1.5Ah of balancing is more than sufficient.

This requires tight BMS inverter coordination. BMS must calculate and send very low CCL values (sub 5A). Inverter must honor these low current requests. Process must continue for 20 to 60 minutes in top 2% of SOC.

Where communication breaks this:

Many inverters have minimum operating currents of 2 to 5A for residential units, sometimes 10A or more for larger systems. BMS requests CCL equals 0.5A for final balancing. Inverter minimum equals 5A. Inverter delivers 5A regardless of request. Voltage rises 10 times faster than BMS expected. Balancing window passed in 3 to 4 minutes instead of 30 to 40 minutes. Balancing completes maybe 10 to 20% of required work. Cells remain 80 to 90% as imbalanced as before. Next charge cycle, same thing happens. Imbalance persists.

Monthly Imbalance Accumulation When Balancing Fails

When balancing does not complete, cells drift apart slowly. This is not dramatic, typically 10 to 20mV per month, but cumulative. Month 1: cells start with 30mV spread, end with 40mV spread. Month 3: 60mV spread. Month 6: 100 to 120mV spread, weakest cell hits low voltage cutoff while strongest cells still at higher voltage, pack has equivalent 3 to 5% lost capacity. Month 12: 180 to 200mV spread, usable capacity reduced by 8 to 12%.

Actual cell degradation: maybe 1 to 2% from normal cycling (LFP degrades slowly). Perceived degradation: 8 to 12% from imbalance. Cells are fine. BMS has balancing capability. Inverter has communication link to coordinate. But because CCL taper does not work correctly, balancing never completes, and system slowly loses capacity anyway.

Communication Loss Modes and Degradation Pathways

Communication between BMS and inverter does not just work or fail. There are three distinct failure modes, each with different consequences for battery health and system availability.

Three Response Strategies to Communication Loss

Mode 1: BMS Opens Contactors

BMS logic: “If I cannot communicate with inverter, I cannot tell it to stop charging or discharging. I cannot enforce my voltage and current limits. Without communication, I have no control. The only safe action is physically disconnect battery.”

BMS detects communication loss (no valid messages for 10 seconds typical), opens main contactors immediately, battery disconnects from inverter under whatever load was present (could be 0A, could be 100A), inverter sees sudden voltage collapse, throws fault codes, system goes offline.

Consequences: Contactor damage from arcing. Opening at 100A DC creates significant arc with contact erosion, heat damage, carbon deposits. Contactors rated for 5,000 to 10,000 cycles at rated current, 1,000 to 2,000 cycles at maximum current. If EMI causes communication glitches 2 to 3 times per week, that is 100 to 150 load switching cycles per year. After 6 to 12 months, contact resistance increases from initial less than 1 milliohm to 5 to 10 milliohms. At 100A, additional 50 to 100W heat dissipation at contacts.

For Full Details Read: Communication Modes: How Your Battery Degrades When Communication Fails

Mode 2: Continue with Last Known State

BMS keeps contactors closed, trusts local protections (over voltage, under voltage, over current, over temperature). Inverter continues operating with last known limits. When communication resumes, limits update to current values.

Advantages: no nuisance trips from EMI glitches, system stays online during transient communication issues, high availability, no contactor cycling damage.

Risk: When BMS state is changing rapidly, stale data causes inverter to continue doing exactly what BMS is trying to prevent. Example: pack temperature rising, BMS dropping CCL from 30A to 15A to 0A as temperature climbs, but communication lost. Inverter continues charging at 30A for 5 minutes beyond when BMS wanted to stop. Temperature climbs faster, forces emergency disconnect.

Mode 3: Hardcoded Default Values

Most common mode. Inverter logic: “Communication lost. Cannot trust stale data indefinitely. After timeout period (10 to 30 seconds typical), fall back to internal default battery settings configured during installation.”

Inverter defaults typically: CVL equals 57.6V for LFP battery type (3.60V per cell for 16S), CCL equals 0.5C or manufacturer specified maximum (50 to 100A), DCL same as CCL.

Why this causes most slow damage: The default CVL is almost always wrong. Inverter default for LFP battery type is 57.6V from cell datasheets showing maximum charge voltage of 3.60 to 3.65V. Technically safe for cells in short term. But most BMS implementations use 56.0 to 56.8V (3.50 to 3.55V per cell) for cycle longevity.

At 3.60V per cell versus 3.50V per cell, calendar aging rate is roughly 30 to 50% higher at 3.60V, SEI layer growth accelerated, capacity fade per cycle increases by 20 to 40%.

If communication glitches 1 to 2 times per week, each time one charge cycle to 57.6V instead of 56.0V. Over 6 months, 25 to 50 charge cycles to 3.60V instead of 3.50V. Accelerated aging from roughly 10% of cycles being at higher voltage. Cumulative capacity loss: 2 to 5% beyond normal aging.

Diagnosis is difficult because BMS logs show “I was sending CVL equals 56.0V every cycle,” inverter logs show “I charged to setpoint, no errors.” Neither log proves inverter temporarily used defaults. You need detailed timestamped logs showing when communication was lost, what CVL was active during each charge, when defaults were used. Most residential systems do not log this detail.

Reader takeaway: Communication loss behavior determines damage type. Understanding the failure mode helps predict long-term consequences.

Systematic Diagnosis

When communication problems occur, 90% are solved by checking configuration and physical layer. Work through diagnostics systematically.

Configuration Verification

1. Protocol selection mismatch: Inverter battery type setting must match BMS protocol exactly. Generic “Lithium” setting might use voltage only control (no CAN communication). “Pylontech” or “CAN” setting enables CAN protocol parsing. Exact name matters: “Pylontech” is not equal to “Pylontech CAN” is not equal to “CAN Protocol” on some inverters.

Full Article: BMS-Inverter Communication Troubleshooting: Proven Solutions to Fix Connection Failures

2. DIP switch positions: Common settings controlled by DIP switches include CAN ID, baud rate, battery type, protocol variant. Documentation may say factory default is DIP 1 to 4 all OFF, but previous installer changed them, factory does not always ship with defaults, or integrator pre configured for different application. Open BMS enclosure, photograph current DIP switch positions, compare against manual for expected configuration.

3. Baud rate mismatch: CAN baud rate must match exactly across all devices on bus. Standard for Pylontech protocol is 500 kbps. BMS at 500 kbps, inverter at 250 kbps means timing is completely wrong, bit periods do not align, every message looks like corrupted garbage.

Physical Verification

1. Termination resistance check: Power off both BMS and inverter. Disconnect CAN cable from one device. Measure resistance between CAN H and CAN L at disconnected cable end. Should read 60Ω ±5Ω. If 60Ω: correct. If 120Ω: missing one termination. If 40Ω: three terminations instead of two. If open circuit: no termination at all.

2. Cable quality and length: Verify cable is twisted pair (cut end and inspect, wires should be twisted together). Check for physical damage (cuts, abrasion, tight bends). Measure actual cable length including routing path. Tight bends damage: CAN cable bent at sharp angle over 90 degrees with small radius breaks individual wire strands if stranded cable, creates impedance discontinuity, damages insulation causing intermittent short between CAN H and CAN L.

3. Connection integrity: Re torque screw terminals to specification or finger tight plus quarter turn with screwdriver. Pull test crimped connections: properly crimped connection withstands 10 to 20 lbs pull, failed crimp pulls out of terminal. Check for corrosion: green copper oxide at connections increases contact resistance from fresh crimp less than 5 milliohms to heavy corrosion over 500 milliohms.

When You Actually Need a CAN Analyzer

What you can diagnose without CAN analyzer: configuration mismatches, physical layer problems, power and ground issues, firmware version known incompatibilities.

When analyzer becomes necessary: physical and configuration verified correct, firmware versions should be compatible, communication still does not work or behaves erratically, need to see actual message content to identify problem.

CAN analyzer connects to CAN bus in parallel, captures all traffic, displays messages with timestamp, CAN ID, data bytes in hex, and error frames. Entry level USB CAN adapters cost $50 to $200. Professional analyzers cost $500 to $2,000.

What you look for: Are messages being transmitted? Is message timing correct (should be every 1000ms ±10%)? Is message content valid (CVL should be reasonable 540 to 580 for 54.0 to 58.0V)? Are messages being acknowledged? Are there error frames?

Barrier for most installers: cost, learning curve (understanding CAN protocol basics, hex to decimal conversion, byte order, Pylontech protocol message structure), time (capturing traffic, analyzing results, interpreting data takes 1 to 3 hours even for experienced users).

The Nuclear Option: Disable Communication and Hardcode

When all diagnostics exhausted, manufacturer support unhelpful, customer needs system operational now, RMA or replacement would take too long or cost too much, accept you are giving up all dynamic protections. This is calculated risk.

Set conservative static limits in inverter: LFP charge voltage 54.4V for 16S (3.40V per cell, below optimal 56.0V but safe, will slightly reduce usable capacity but will not overcharge). Charge current limit to 0.3 to 0.5C. Discharge current same. Low voltage cutoff 48.0V for 16S (3.00V per cell, provides margin before 2.50V actual damage threshold).

Disable BMS communication in inverter (menu setting typically “Battery communication: Disabled” or “Use manual battery settings”). Inverter will not attempt CAN communication, will use hardcoded values, will rely on voltage sensing only for charge termination.

Enable basic monitoring in inverter: monitor pack voltage, pack current, basic temperature. Set alarms for high voltage 57.0V, low voltage 46.0V, high current at nameplate limit, high temperature 50°C.

What you give up: cell level protection (BMS cannot dynamically adjust limits based on highest or lowest cell), dynamic temperature response (inverter temperature sensor measures ambient or pack surface, cannot respond to internal cell temperature), imbalance detection (BMS cannot request reduced current when cells diverge), state of charge accuracy (inverter calculates SOC from voltage, inaccurate for LFP flat curve), automatic balancing coordination (no CCL taper for top balance, quarterly manual top balance required).

Hardcoding is not permanent solution. It is workaround with ongoing maintenance requirements. Do it eyes open, document thoroughly, set customer expectations correctly, plan for ongoing manual maintenance.

Conclusion

The BMS and inverter were designed independently, by different companies, with different goals, and nobody owns the integration. This is not a technical problem that can be solved with better engineering. It is a systemic problem in how the industry develops and sells components.

BMS manufacturer goals: protect cells (cells are most expensive component, cell damage creates warranty liability, battery longevity is primary differentiator). BMS optimized for cell survival, not system availability or performance.

Inverter manufacturer goals: deliver rated power and keep customers happy (inverter capability is marketing headline, customer satisfaction depends on system doing what they expect, support costs driven by customer calls about system not working). Inverter optimized for availability and user satisfaction, not absolute cell protection.

Where these goals conflict: conservative limits versus rated performance, disconnect on ambiguity versus availability, absolute protection versus usable capacity. Communication is the battleground where these conflicts play out. BMS sends limits. Inverter decides whether to respect them. Battery loses when they disagree.

What “compatible” actually means: marketing claim says these devices will work together. Technical reality is they use same CAN message IDs, data fields in approximately same byte positions, baud rate is 500 kbps, maybe tested together once in ideal conditions for few hours. Field reality is works on bench test, works in 70 to 80% of installations, fails in 20 to 30% of installations, or works initially then fails after weeks or months when edge case conditions occur.

Compatible is spectrum, not binary. There is no certification, no compliance test, no standard definition of compatible. It is marketing term, not technical guarantee.

The practical path forward for installers: verify configuration obsessively, physical layer first (90% of problems are configuration and physical), log everything (cannot diagnose what you did not record), set realistic customer expectations (compatible means probably works, not guaranteed), know when to hardcode and walk away.

For integrators: design for diagnosability (choose components with diagnostic access, include monitoring infrastructure in initial design), open protocols unless proven support (proprietary acceptable if manufacturer support verified through multiple installations and responsive service), plan for communication loss (Mode 2 or coordinated watchdog preferred), build institutional knowledge (document which combinations work reliably, share with team, learn from failures), budget for troubleshooting (include contingency in quotes for communication integration).

The communication link between BMS and inverter is not just data transfer. It is negotiation over control authority. There is no protocol that resolves these conflicts. They are fundamental disagreements about priorities. The best we can do is understand what each device is trying to accomplish, design systems where conflicts are rare, monitor for signs of conflict, intervene before conflict causes damage.

Understanding how the negotiation fails helps you design systems that fail gracefully instead of destroying cells. The gap between what BMS sends and what inverter does with it, that 3 second lag, that CVL averaging, that default fallback value, that is where batteries get damaged while both devices report normal operation. Close that gap through design, catch failures through monitoring, manage expectations through honest communication with customers.

Hi, i am Engr. Ubokobong a solar specialist and lithium battery systems engineer, with over five years of practical experience designing, assembling, and analyzing lithium battery packs for solar and energy storage applications, and installation. His interests center on cell architecture, BMS behavior, system reliability, of lithium batteries in off-grid and high-demand environments.