Introduction

You’ve just finished wiring a 48V lithium bank for an off-grid solar system. The charge controller, a well-known MPPT unit you’ve installed dozens of times, has a “lithium” profile in the settings menu. You select it, set bulk voltage to 54.4V, absorption to 54.4V, float to 53.6V, punch in a 2-hour absorption time, and call it done. The display shows the familiar progression you’ve seen on every lead-acid job for the past decade: Bulk → Absorption → Float.

Here’s what actually just happened: You configured a charging framework designed to solve lead-acid sulfation, manage hydrogen and oxygen gas recombination, and compensate for continuous self-discharge. Your lithium battery has exactly none of these problems. The charge controller will march through its three-stage routine because that’s how it’s programmed, but what’s happening inside those lithium iron phosphate cells bears almost no resemblance to what those stage names suggest.

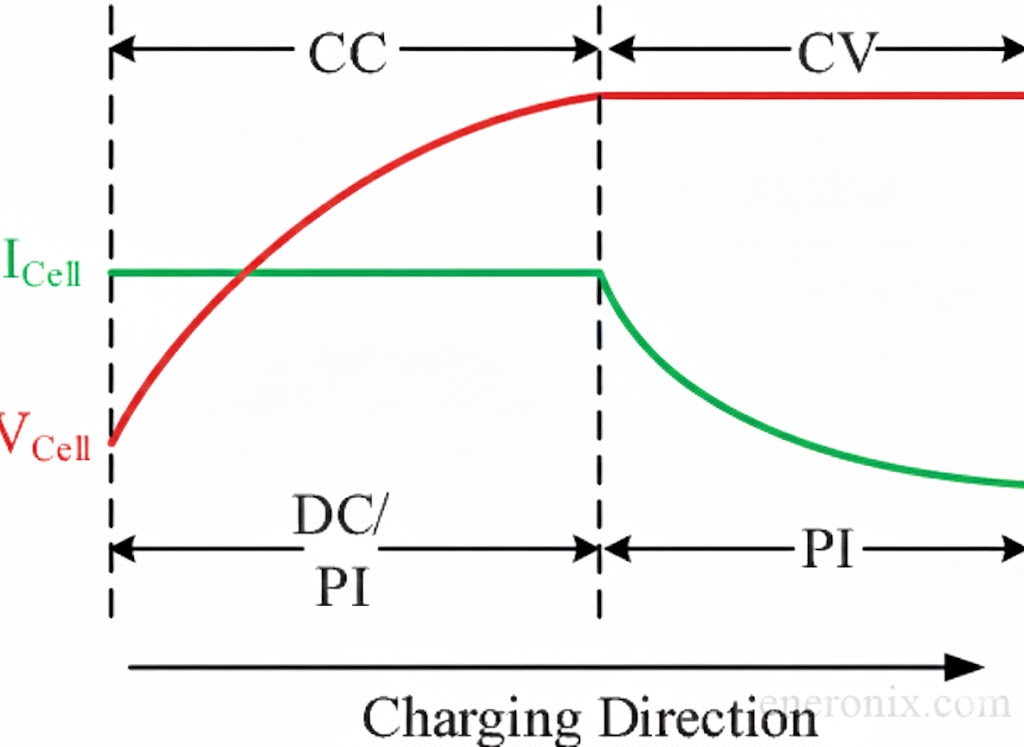

Lithium batteries do not require three charging stages. They charge using a two-stage constant-current, constant-voltage (CC/CV) algorithm. Bulk, absorption, and float are legacy labels carried over from lead-acid systems.

I’m not saying the approach doesn’t work, it does. Millions of lithium batteries charge successfully using bulk/absorption/float profiles every day. But understanding the mismatch between what your charge controller thinks it’s doing and what’s actually happening at the electrochemical level is the difference between a system that works adequately for 8-10 years and one that works optimally for 12-15 years. The difference isn’t dramatic failures or blown BMSs. It’s subtle: unnecessary time at elevated voltage accelerating calendar aging, insufficient balancing time allowing cells to drift apart, or float stages that solve problems lithium doesn’t have while creating problems it does.

In practice, what most installers don’t realize is that “absorption” for lithium isn’t about waiting for chemistry to catch up like it is with lead-acid. The battery reaches 95% state of charge within five minutes of hitting absorption voltage. The remaining hour or two of absorption time? That’s not charging, that’s giving the passive balancing circuits time to equalize cell voltages at 30-100 milliamps. And “float”? Lithium self-discharge is under 3% annually. There’s nothing to maintain. That float voltage sitting at 53.6V for hours every afternoon is actually accelerating calendar aging by keeping cells at elevated voltage and high state of charge.

This post, and this series, explains what bulk, absorption, and float stages were designed to do for lead-acid chemistry, how lithium chemistry responds completely differently during each stage, and why the three-stage model doesn’t translate well. By the end, you’ll understand why your charge controller has three stages for a battery chemistry that only needs two, and how that understanding changes the way you configure systems.

What Bulk, Absorption, Float Were Actually Designed to Solve

Before we can understand why these three stages don’t fit lithium well, we need to understand what problems they were originally designed to solve. Bulk, absorption, and float charging exist because of three specific challenges in lead-acid battery chemistry. If you’ve only worked with lithium, some of this might seem strange, and that’s exactly the point.

1. The Sulfation Problem (Why "Bulk" Exists)

Lead-acid batteries don’t accept charge easily when discharged. The problem is sulfation. During discharge, lead sulfate crystals form on the battery plates. These PbSO₄ crystals create a resistive barrier that you have to push through during recharge. When you try to charge a discharged lead-acid battery, you’re not just moving charge back in, you’re fighting through this sulfate layer to convert PbSO₄ back into active lead and lead dioxide.

This conversion is slow and requires sustained high current to push through the resistance. In practice, what I see is voltage rising gradually during bulk charging, not because the battery is approaching full charge, but because the chemical conversion process is breaking down sulfation resistance. A deeply discharged lead-acid battery might sit at 12.2V for the first hour of charging, slowly climbing to 12.8V, then 13.5V, as sulfation breaks down and active material becomes available again.

The bulk stage continues until voltage reaches approximately 14.4-14.8V for a 12V battery, the point where the next problem begins. This isn’t an arbitrary voltage. It’s the threshold where water in the electrolyte starts to break down, which brings us to absorption. The bulk stage exists specifically to overcome the sulfation barrier that builds up during every discharge cycle. Without sustained high current pushing through this resistance, you’d never fully charge a lead-acid battery. The stage ends at a chemistry-defined transition point, not at some installer-chosen voltage.

2. The Gas Recombination Problem (Why "Absorption" Exists)

Above about 14.4V, lead-acid batteries start generating hydrogen and oxygen gas as water electrolyzes. In flooded batteries, you can see this as bubbling in the cells. In sealed AGM or gel batteries, these gases need to recombine internally, oxygen migrating to the negative plate to react with hydrogen and reform water.

This recombination process is slow. The chemistry can’t keep up with the rate of gas generation if you maintain high current. Hold the voltage constant at the gassing threshold (14.4-14.8V), and current naturally decreases as the recombination rate catches up with the generation rate. This is absorption, you’re literally waiting for slow chemical kinetics to absorb the charge without building up dangerous gas pressure.

A typical lead-acid absorption phase lasts 2-4 hours because that’s how long the recombination chemistry takes. Cut it short, and you haven’t actually charged the battery fully, gases evolved instead of charge being stored. The current tapering during absorption isn’t just about the battery approaching full charge, it’s about the rate at which oxygen and hydrogen can recombine being slower than the rate at which they’re being generated.

This is also why absorption voltage and time matter so much for lead-acid. Too low or too short, and you undercharge. Too high or too long, and you generate gas faster than it can recombine, building pressure in sealed batteries or losing water in flooded batteries. I’ve seen installers cut absorption time to 30 minutes thinking they’re being efficient, then wonder why the battery loses capacity within six months. The chemistry needs that time. It’s not arbitrary, it’s not conservative engineering margin, it’s the actual kinetic limitation of gas recombination reactions happening inside the battery.

3. The Self-Discharge Problem (Why "Float" Exists)

Lead-acid batteries self-discharge continuously, losing roughly 5-15% of their charge per month just sitting idle. This happens because of grid corrosion, the lead grids supporting the active material slowly corrode in the sulfuric acid electrolyte, creating parasitic reactions that consume charge.

For a battery in standby service, UPS systems, emergency lighting, backup power, this means the battery would be substantially discharged when you actually need it if left alone for weeks or months. Float charging solves this by providing continuous trickle current at a lower voltage (typically 13.2-13.8V for 12V batteries) that exactly balances the self-discharge rate.

The float voltage is carefully chosen: high enough to offset self-discharge, but low enough to minimize gassing and water loss. Too high, and you’re overcharging and generating gas continuously. Too low, and self-discharge wins and the battery slowly depletes. Float charging is genuine maintenance; it’s actively fighting an ongoing chemical process that would otherwise discharge the battery.

I’ve measured this directly on lead-acid backup systems. Disconnect float charging from a fully charged battery, come back three months later, and you’ll find it at 50-60% state of charge. The battery didn’t power anything. It just sat there corroding internally, parasitic reactions consuming the stored energy. Float isn’t optional for lead-acid in standby applications; it’s required to keep the battery ready for use. Without it, you’d need to manually charge the battery every few weeks, which defeats the purpose of having standby power.

Each stage addresses a specific electrochemical limitation. Bulk overcomes sulfation resistance and accomplishes the heavy lifting of charge transfer while managing the slow conversion chemistry. Absorption holds at the gassing threshold while waiting for recombination kinetics to catch up, ensuring charge is stored rather than lost as evolved gas. Float provides continuous maintenance current to counteract the constant drain of grid corrosion and self-discharge. The framework is elegant because it’s matched to the chemistry. Sulfation creates resistance, bulk pushes through it. Gassing limits charge acceptance at high voltage, absorption manages the kinetic bottleneck. Self-discharge drains the battery continuously; float maintains full charge during standby.

Now here’s where it gets interesting: lithium batteries have none of these problems. Not sulfation, not slow gas recombination, not significant self-discharge. So why are we using the same three-stage framework?

How Lithium Chemistry Is Fundamentally Different

The three-stage charging framework exists to solve sulfation, gassing, and self-discharge. Lithium iron phosphate chemistry has none of these issues. Understanding why requires looking at what’s actually happening inside a lithium cell during charge and discharge, which is fundamentally different from lead-acid electrochemistry.

1. No Sulfation = No Bulk "Problem"

Lithium batteries use intercalation, not chemical conversion. During discharge, lithium ions (Li⁺) leave the graphite anode, travel through the electrolyte, and insert themselves into spaces within the cathode’s crystal structure (lithium iron phosphate, LiFePO₄). During charging, the process reverses, ions leave the cathode and re-insert into the graphite layers at the anode.

This is a physical insertion process, not a chemical transformation like converting lead sulfate back to metallic lead. There’s no resistive barrier that builds up during discharge and needs to be overcome during charging. The graphite layers at the anode and the olivine structure of the LiFePO₄ cathode remain structurally intact throughout cycling. Ions move in and out of existing spaces within these structures.

What this means practically: A lithium battery accepts charge current readily from completely discharged to nearly full. Internal resistance stays relatively constant across the entire state of charge range. You don’t see the slow voltage rise during early charging that characterizes lead-acid bulk phase. Voltage follows a predictable curve based on how many lithium ions are in the anode versus the cathode, not based on breaking down chemical resistance.

In practice, I’ve watched LiFePO₄ cells accept full rated current (0.5-1C) at 10% state of charge just as readily as they do at 70% state of charge. The limitation isn’t sulfation resistance, it’s ionic conductivity in the electrolyte and diffusion rates into particle interiors, which are fairly constant throughout the charge cycle. A 100Ah pack will accept 50A at 10% SOC with the same ease it accepts 50A at 70% SOC. This is why lithium charges in 1.5 hours what takes lead-acid 4-6 hours. There’s no resistance barrier to fight through, just straightforward ion movement at maximum safe current until you approach the voltage limit.

2. No Gassing = No Absorption "Problem"

LiFePO₄ chemistry has a very stable voltage window. The maximum cell voltage (3.65V per cell, or 14.6V for a 12V pack) stays well below the voltage where electrolyte decomposition occurs. There’s no water to electrolyze like in lead-acid, and the organic electrolyte solvents remain stable at normal charging voltages.

This is why lithium cells are sealed with pressure relief vents for safety, not because they expect continuous gassing like flooded lead-acid. Gas generation only occurs during abuse conditions, overcharge beyond safe voltage limits, internal shorts causing local heating, or manufacturing defects. In normal cycling within the 2.5-3.65V per cell window, gas evolution is essentially zero.

What this means for charging: There’s no recombination delay to manage. When you apply current at constant voltage, the current tapers because you’re approaching thermodynamic equilibrium, the ion concentration gradient between anode and cathode is flattening, not because you’re waiting for gases to recombine. The current taper in lithium is fast (minutes to reach 95% SOC at constant voltage) compared to lead-acid absorption (hours waiting for recombination).

I’ve measured LiFePO₄ cells reaching 95% state of charge within 5-10 minutes of hitting 3.60V per cell. The remaining current taper from, say, 10A down to 0.5A happens in another 30-45 minutes as the last few percent of capacity fills. There’s no chemistry waiting to catch up, just straightforward approach to equilibrium. When installers set 2-4 hour absorption times for lithium because “that’s how long absorption takes,” they’re applying lead-acid gas recombination timing to a chemistry that finished charging in the first 10 minutes. The remaining time isn’t absorption in any chemical sense, it’s waiting for something entirely different that we’ll cover in the next post.

3. Negligible Self-Discharge = No Float "Problem"

LiFePO₄ self-discharge is typically under 3% annually, that’s roughly 0.25% per month compared to lead-acid’s 5-15% per month. The mechanism is completely different too. Lead-acid self-discharge comes from grid corrosion, an ongoing electrochemical reaction. Lithium self-discharge comes from side reactions at the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) layer on the anode surface, a passive film that forms during initial cycling and then remains relatively stable.

This SEI layer does slowly consume a tiny amount of lithium over time through parasitic reactions, but at a rate that’s negligible for practical purposes. A fully charged LiFePO₄ battery left sitting for six months will still have 97-99% of its charge remaining. A lead-acid battery in the same situation would have lost 30-50% of its charge.

What this means for maintenance: There’s nothing to maintain. No continuous float current is needed to fight self-discharge. If you disconnect a lithium battery after charging and come back three months later, it’s essentially at the same state of charge. Float charging isn’t compensating for an ongoing loss; it’s just keeping the battery at elevated voltage for no chemistry-based reason.

In installations where I’ve monitored lithium banks that sit idle for extended periods, seasonal off-grid cabins, backup power systems that rarely activate, the batteries maintain voltage and capacity for months without any charging input. I’ve seen systems come back online after four months of winter storage, batteries still reading 13.3V and delivering full capacity on the first discharge cycle. This is fundamentally incompatible with the need for continuous float that defines lead-acid standby applications. There’s no parasitic drain to compensate for, no grid corrosion consuming charge, no chemical reason to apply continuous maintenance current.

The framework that made perfect sense for lead-acid, three stages addressing three specific problems, becomes a mismatch when applied to lithium chemistry that doesn’t have any of those problems.

What Lithium Actually Uses Instead

Lithium doesn’t need three stages. It uses simple CC/CV, constant current followed by constant voltage. That’s it. Two stages, not three.

CC/CV charging method for lithium-ion batteries

1. Constant Current (CC) phase:

Apply maximum safe current (typically 0.5C for LiFePO₄, though some cells handle 1C or higher) until pack voltage reaches the target limit, usually 14.2-14.4V for 12V systems (3.55-3.60V per cell). Voltage rises predictably during this phase as the ion concentration ratio shifts. This phase delivers roughly 85-90% of the battery’s capacity.

What this looks like in practice: You’re charging a 100Ah pack at 50A (0.5C). At 20% SOC, pack voltage reads 13.2V. As charging continues, voltage climbs steadily, 13.6V at 40% SOC, 14.0V at 70% SOC, then more rapidly toward 14.4V as you approach 90% SOC. Current stays constant at 50A the entire time, that’s what constant-current means. The voltage rise isn’t from breaking down resistance like lead-acid sulfation, it’s the thermodynamic result of lithium ions accumulating in the anode and depleting from the cathode. The electrochemical potential difference between the electrodes increases as the concentration imbalance grows.

This phase is fast. From 10% to 90% SOC at 0.5C takes roughly 1.6 hours of actual charging time. At 1C, some modern cells do this in under an hour. There’s no sulfation barrier slowing things down, no chemical conversion bottleneck, just straightforward ion movement limited only by ionic conductivity and safe current limits.

2. Constant Voltage (CV) phase:

Hold voltage at the target limit and let current taper naturally as the battery approaches equilibrium. Current decays exponentially from the CC phase current down to nearly zero. This phase adds the final 10-15% of capacity and happens quickly, most of it in the first 10-15 minutes, with a long tail as you approach 100%.

What this looks like: Pack hits 14.4V at roughly 90% SOC, charge controller switches to CV mode. Current immediately begins dropping, 50A to 40A to 30A in the first few minutes as the battery rapidly absorbs that easily accessible remaining capacity. Within 10 minutes you’re at 95% SOC and current is down to 15A. Another 20 minutes gets you to 98% SOC at 5A. The final 2% takes another 30-60 minutes as current tapers from 5A to 2A to 0.5A, chasing that asymptotic approach to 100% SOC.

That’s the entire charging algorithm. No bulk stage fighting sulfation, no absorption stage waiting for recombination, no float stage compensating for self-discharge. Just CC until voltage limit, then CV until current tapers to an acceptable endpoint (typically 0.02-0.05C, or when you decide charging is “complete enough” for your application).

Also Read: The Lithium Battery Architecture Handbook: A Systems Guide to Cells, BMS, and Internal Engineering

Comparing the Two Chemistries Side-by-Side

| Aspect | Lead-Acid | Lithium (LiFePO₄) |

| Charging Mechanism | Chemical conversion (PbSO₄ → Pb/PbO₂) | Physical intercalation (Li⁺ insertion) |

| Discharge Resistance | High (sulfation barrier) | Low (constant throughout) |

| Charge Acceptance | 0.1-0.2C when discharged | 0.5-1C from empty to full |

| Gas Generation | Above 14.4V (water electrolysis) | Essentially none in normal range |

| Charging Speed | 6-10 hours (0-100%) | 1.5-2.5 hours (0-100%) |

| Self-Discharge Rate | 5-15% per month | <3% per year |

| Maintenance Needs | Continuous float required | No maintenance needed |

| Voltage Stages Needed | Three (bulk/absorption/float) | Two (CC/CV) |

| Absorption Duration | 2-4 hours (recombination) | 10-15 minutes (charge), plus balancing time |

| Float Purpose | Offset self-discharge | Not needed (can be harmful) |

Why Controllers Still Show Three Stages

If lithium only needs two stages, why does every charge controller display show bulk, absorption, and float? Economics and compatibility.

Charge controllers are designed to handle multiple battery chemistries with the same hardware and firmware architecture. Building separate charging algorithms for different chemistries is more complex and expensive than adjusting voltage setpoints within a common three-stage framework. The market wants one controller that works with flooded lead-acid, AGM, gel, and lithium. Manufacturers deliver that by building one state machine and modifying parameters.

What a “lithium profile” really does is modify the voltages and timings of the existing bulk/absorption/float state machine. Bulk becomes the CC phase by setting bulk voltage to your target (14.2-14.4V). Absorption becomes the CV phase by setting absorption voltage to the same value. Float becomes either disabled, set to a low standby voltage, or set equal to absorption to prevent stage cycling.

The controller display still shows “bulk,” “absorption,” and “float” because that’s how its state machine is programmed. The firmware was written once for lead-acid, then adapted for other chemistries by changing numbers in lookup tables. But what’s actually happening inside the lithium battery during these stages is completely different from what happens inside a lead-acid battery. The stage names remain the same, the underlying electrochemistry is entirely different.

I’ve configured hundreds of these systems. The controller dutifully displays “Bulk” while delivering constant current, switches to “Absorption” when it hits voltage limit and begins CV tapering, then drops to “Float” after the absorption timer expires or tail current threshold is met. The customer sees familiar terminology. The battery just sees CC/CV with an optional standby voltage at the end. The translation works, but only if you understand what’s actually happening behind those legacy labels.

1. The Translation Problem

Understanding that lithium uses two-stage CC/CV while your charge controller speaks three-stage bulk/absorption/float creates a translation problem. The stage names suggest functions that don’t match what’s happening chemically, and this leads to configuration errors based on lead-acid thinking rather than lithium reality.

2. Applying Lead-Acid Logic to Lithium

The most common mistake I see:

setting long absorption times (2-4 hours) because “that’s how long absorption takes” in lead-acid systems. Installers carry over timing from gas recombination requirements that don’t exist in lithium. The result is keeping cells at high voltage unnecessarily. The charging was mostly done in the first 10 minutes of CV phase, everything beyond that is either waiting for cell balancing circuits to work (which has nothing to do with charging chemistry) or just holding the battery at elevated voltage for no reason.

Second mistake:

enabling float because “batteries need float to stay charged.” Lead-acid absolutely needs this; the battery loses 5-15% monthly without it. Lithium loses under 3% annually. Float isn’t maintaining charge against self-discharge, it’s exposing lithium to sustained high SOC and elevated voltage, accelerating calendar aging. Thousands of hours per year at 13.6V or higher, degrading the SEI layer and stressing the cathode structure when the battery doesn’t need any maintenance current.

Third mistake:

expecting bulk voltage and absorption voltage to be different because lead-acid has a gassing threshold that defines a clear transition point. Installers set bulk to 14.6V and absorption to 14.4V, or some similar split, thinking absorption is the “finishing stage” that should use lower voltage. Lithium doesn’t have a gassing threshold separating these phases. The voltages should be the same because you’re just switching from CC to CV at your chosen voltage limit. Setting them different creates an unnecessary voltage drop at the stage transition that serves no purpose.

The Actual Problems This Creates

These configuration errors don’t cause immediate failures. That’s why they persist. The BMS doesn’t trip, the battery charges, the system works. But the problems accumulate over years:

Insufficient balancing time causes cell drift. Cells that start within 20mV of each other at installation spread to 50mV, then 80mV, then 120mV over months of cycling. Eventually one cell hits BMS overvoltage protection before the pack is full, robbing you of usable capacity. The customer complains “battery only charges to 85% now” and you’re troubleshooting for equipment failure when the real problem is cells that drifted apart because absorption time was too short for the passive balancing circuits to keep up.

Excessive high-voltage exposure accelerates calendar aging. A pack configured with float at 13.6V, sitting there for 5-6 hours every sunny afternoon, ages 20-30% faster than a pack that rests at lower voltage between charge cycles. The difference isn’t visible in year one or two. By year five, one pack is at 85% capacity while the properly configured pack is still at 92-94%. By year eight, one pack is reaching end-of-life while the other has years of service remaining.

Read Also: Why Most Solar-Battery Systems Fail Before Year 2

BMS trips from configurations that push too close to limits. Setting bulk/absorption to 14.6V (3.65V per cell) because “that’s what the spec sheet says is maximum” leaves no margin for cell imbalance or measurement tolerance. One cell measure slightly high, hits BMS protection, charging stops abruptly. The installer sees intermittent charging failures and starts replacing hardware when the actual problem is configuration leaving no headroom.

Misdiagnosis wastes time and money. “Absorption won’t complete” gets interpreted as a gas recombination problem because that’s what it means in lead-acid. You check charge controller settings, look for shorted cells, measure absorption current expecting to find something preventing gas recombination from catching up. In reality, absorption completed quickly, the remaining time is either waiting for balancing circuits or hitting BMS thermal limits because the battery box is poorly ventilated. You’re troubleshooting the wrong problem because the stage name suggests chemistry that isn’t happening.

What Understanding the Mismatch Gets You

The three-stage framework can work for lithium, but only if you understand that the stage names are inherited terminology that don’t match what’s actually happening chemically. This understanding changes how you configure systems:

Bulk isn’t overcoming sulfation, it’s CC charging. Set the voltage based on BMS limits and balancing activation thresholds, not gassing considerations that don’t apply.

Absorption isn’t waiting for gas recombination; it’s CV taper plus balancing time. Set the duration based on how much balancing time your cells need, not on some universal “absorption takes 2-4 hours” rule from lead-acid experience.

Float isn’t fighting self-discharge; it’s an optional standby state that probably shouldn’t exist for most lithium applications. Disable it if possible, minimize it if required, and never assume lithium needs maintenance current the way lead-acid does.

Configure based on what the chemistry actually needs, not what the stage names suggest. That’s the difference between adequate and optimal.

What’s Coming in This Series

This post establishes the core problem: lithium batteries charge using a two stage CC/CV process, yet we continue to force them into a three-stage bulk/absorption/float framework designed for lead acid chemistry.

Next, we’ll examine the bulk/CC phase why lithium accepts high current so easily, why it charges dramatically faster than lead acid, and how BMS pre throttling actually works. When charge current suddenly drops to 8 A at 13.8 V on a clear day, that isn’t faulty equipment it’s the BMS protecting an imbalanced cell. We’ll also cover temperature limits and how to correctly diagnose “won’t accept charge” complaints.

Then we’ll move to the absorption/CV phase. For lithium, charging is essentially complete within about ten minutes of reaching CV. What takes longer isn’t charging its cell balancing. We’ll calculate absorption time based on real balancing currents (typically 30–100 mA), not inherited lead acid rules. This is where most lithium systems are misconfigured.

After that comes the float problem: why holding lithium at elevated voltage accelerates degradation through SEI layer growth and cathode stress. We’ll show why time at high voltage matters more than cycle count, and the few edge cases where float may still make sense.

Finally, we’ll tie everything together with practical configuration guidance specific voltage targets with real margins, absorption times based on cell size and imbalance, and application specific recommendations for off grid, RV, and backup systems. Temperature compensation must be zero. Equalization must be disabled. These are not preferences; they are requirements.

Understanding that the three-stage framework is a workaround not a perfect fit is what separates adequate installations from optimal ones. That difference is not theoretical. It’s the difference between 8 10 years of service and 12 15 years from the same hardware.

Hi, i am Engr. Ubokobong a solar specialist and lithium battery systems engineer, with over five years of practical experience designing, assembling, and analyzing lithium battery packs for solar and energy storage applications, and installation. His interests center on cell architecture, BMS behavior, system reliability, of lithium batteries in off-grid and high-demand environments.