Introuction

Lithium battery packs rarely fail all at once. Instead, they slowly fall apart as individual cells drift in voltage and capacity, degrading quietly until performance drops or something goes seriously wrong. Preventing that breakdown is the job of the Battery Management System (BMS), and at the heart of every smart BMS is one critical feature: smart cell balancing algorithms.

In this article, I’m not just going to say that balancing matters. We’ll dig into how modern balancing algorithms actually work how they monitor cell voltages in real time, estimate state of charge, decide which cells need attention, and redistribute energy to keep the entire pack healthy. You’ll see how these systems extend battery life, prevent overvoltage damage, and adapt to real-world conditions like temperature changes and uneven aging.

By the end, you’ll understand not only why smart balancing is essential, but how it works under the hood. With clear explanations, diagrams, and real-world examples, this guide is for anyone who wants to move past surface-level advice and understand the logic that keeps high-performance battery packs running safely and efficiently.

Understanding the Basics of Battery Balancing

At its simplest, battery balancing is about keeping every cell in a pack operating within the same electrical parameter. A lithium battery pack is only as strong as its weakest cell, and when cells drift apart, the entire pack suffers either by losing usable capacity or by being pushed into unsafe operating conditions.

What Is Battery Balancing?

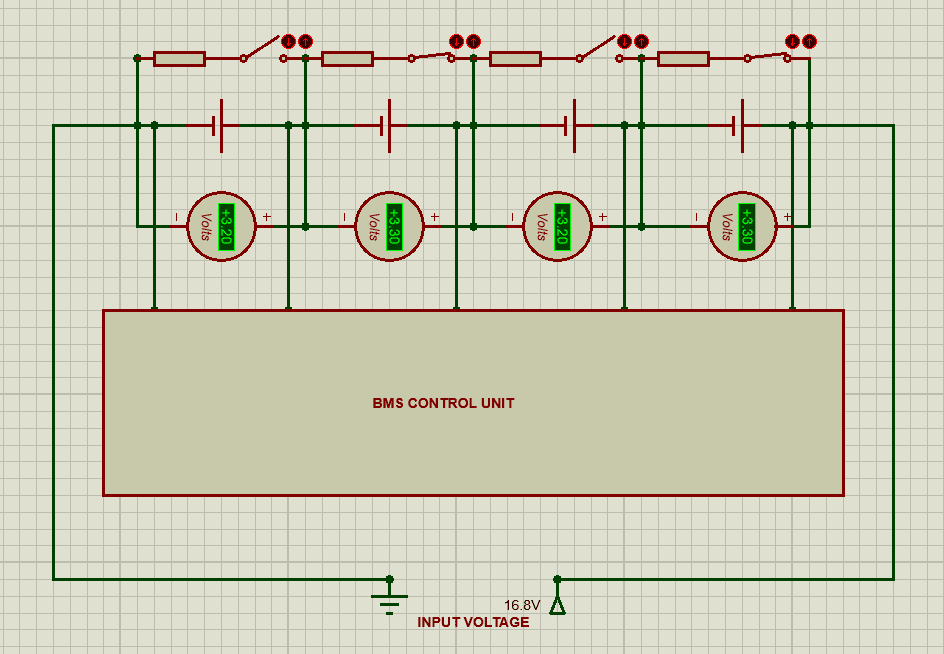

Battery balancing is the process of equalizing the voltages and indirectly the usable capacity of individual cells in a battery pack. Since modules are typically connected in series to increase the packs voltage, the pack’s usable energy is limited by the cell that reaches its voltage limits first. If one cell charges faster or discharges sooner than the rest, it effectively bottlenecks the entire system.

For more knowledge on lithium packs and engineering read this:

A balancing system monitors each cell and takes action to bring them back into alignment, ensuring that no single cell is overcharged, over-discharged, or prematurely aged. This results in higher usable capacity, improved safety, and significantly longer pack life.

Also Read: The Lithium Battery Architecture Handbook

Why Cells Become Imbalanced?

Even cells that start out identical don’t stay that way for long. Imbalance is inevitable, and it usually comes from a combination of small, compounding effects:

1.Manufacturing variations

Tiny differences in internal resistance, capacity, and chemistry mean cells age at slightly different rates, even within the same batch.

2.Temperature differences:

Cells closer to heat sources or with less cooling experience faster degradation, which accelerates voltage drift over time.

3.Charging and discharging patterns:

High currents, partial charge cycles, and uneven load distribution can cause certain cells to hit voltage limits earlier than others. Over hundreds or thousands of cycles, these effects stack up. Without balancing, the weakest cell increasingly defines the usable range of the entire pack.

Types of Battery Balancing

Balancing methods generally fall into two categories: passive and active. Both aims to reduce voltage spread between cells, but they do so in very different ways.

Passive (Resistive) Balancing

Passive balancing is the simplest and by far the most widely used balancing approach in lithium battery packs. When a cell’s voltage rises above a defined threshold, the BMS activates a bleed circuit, typically a resistor placed across the cell. This resistor draws current from the cell, converting the excess energy into heat and slowing that cell’s rise in voltage while the rest of the pack continues charging.

In practice, passive balancing usually occurs near the top of charge. Once the highest-voltage cells reach their limit, the BMS selectively bleeds them down, giving lower-voltage cells time to catch up. This approach works well when the imbalance between cells is relatively small, which is often the case in well-designed packs or systems that are balanced frequently.

The biggest advantage of passive balancing is its simplicity. The hardware is minimal, the control logic is straightforward, and the overall cost is low. This makes it an attractive choice for consumer electronics, power tools, and many off-the-shelf BMS solutions where size, cost, and reliability matter more than maximum efficiency.

However, passive balancing comes with clear trade-offs. Because the excess energy is dissipated as heat, balancing becomes less efficient as pack size and energy increase. The bleed current is also typically limited to avoid excessive heating, which means balancing can be slow especially in large battery packs or systems with significant cell mismatch. In those cases, passive balancing may struggle to keep up, allowing imbalance to accumulate over time.

Despite these limitations, passive balancing remains a practical and effective solution for many applications. When properly sized and paired with reasonable charge rates, it provides adequate protection and longevity without the complexity of more advanced balancing methods.

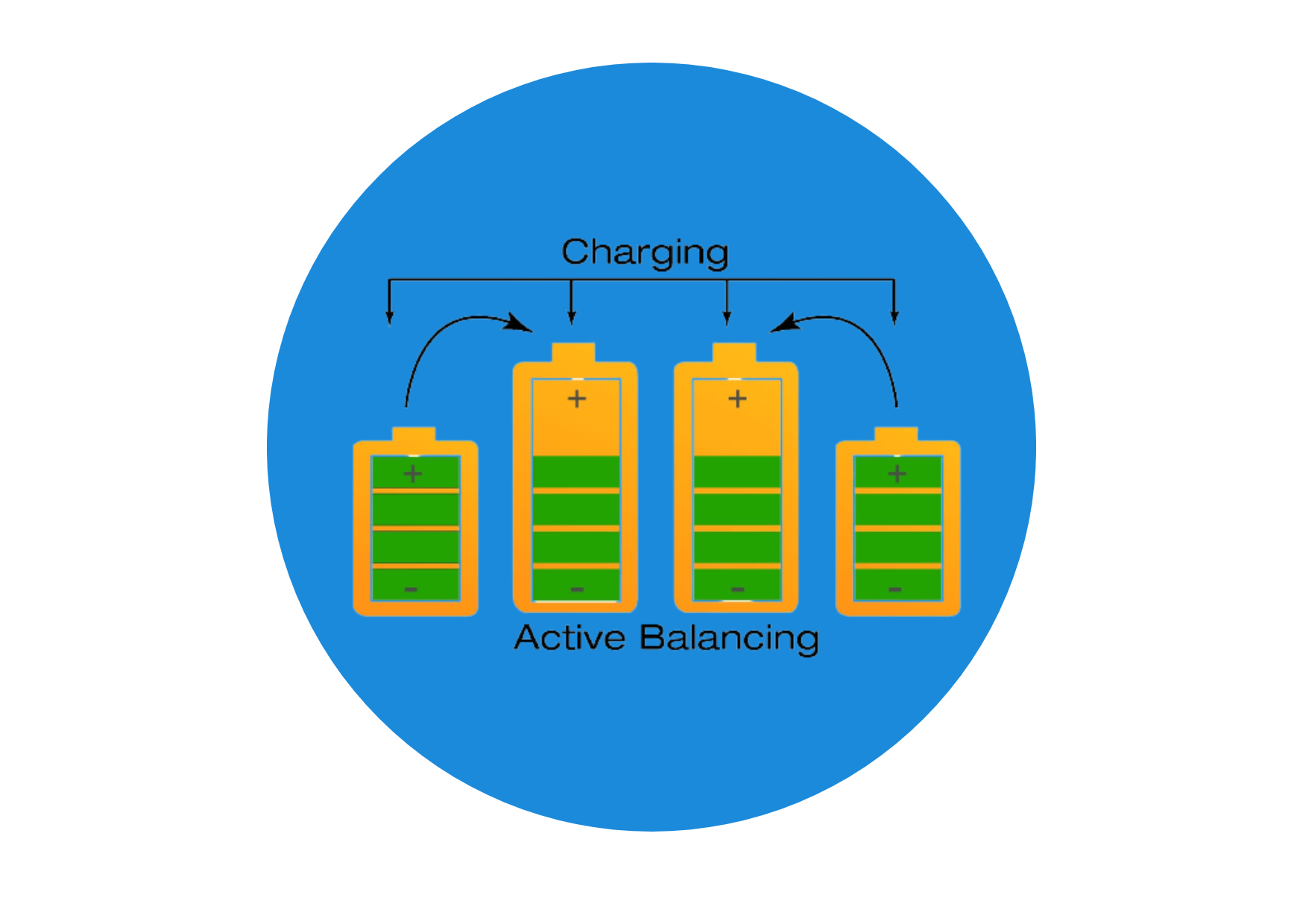

Active Balancing

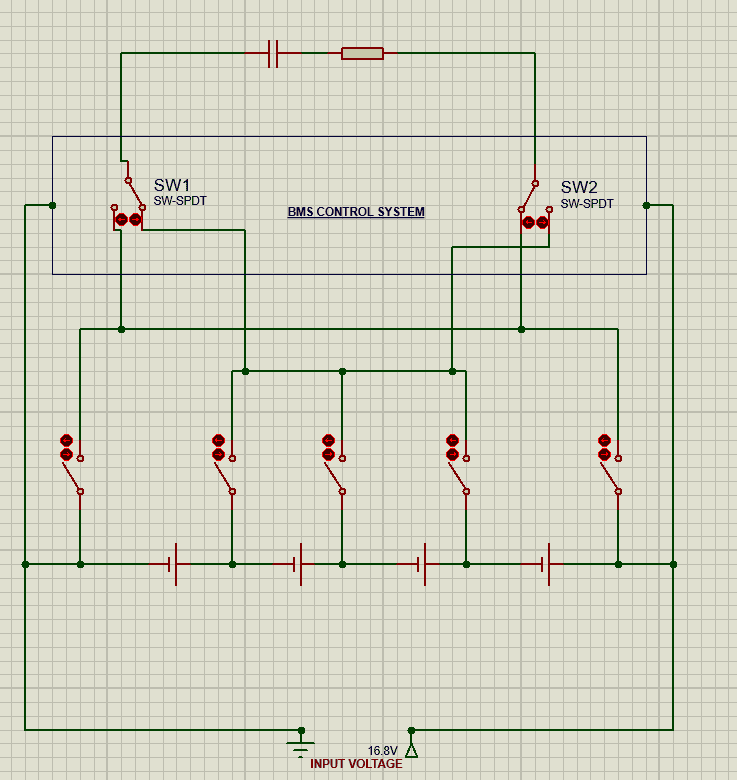

Active balancing takes a more sophisticated approach to keeping cells aligned by redistributing energy instead of wasting it. Rather than bleeding off excess charge as heat, active systems move energy from higher-voltage cells to lower-voltage ones using components such as capacitors, inductors, or dedicated DC-DC converters. The goal is the same reduce voltage spread across the pack but the method is far more efficient.

In an active balancing system, the BMS continuously evaluates which cells have excess energy and which ones need it. Energy can be transferred directly between cells, between a cell and the pack bus, or through an intermediate storage element, depending on the architecture. This allows imbalance to be corrected more quickly and with far less energy loss compared to passive methods.

The primary advantage of active balancing is efficiency, which becomes increasingly important as pack size and energy increase. Because energy is reused rather than dissipated, active balancing is well suited for large battery packs, high-cycle applications, and systems where maximizing usable capacity matters such as electric vehicles, energy storage systems, and high-performance industrial equipment.

Active balancing also offers greater flexibility in when balancing occurs. Unlike passive systems that typically operate only near the top of charge, active systems can balance during charging, discharging, or even while the pack is at rest. This makes it easier to control imbalance early, before it grows large enough to limit performance or accelerate aging.

The trade-off is complexity. Active balancing requires more components, tighter control algorithms, and careful design to manage efficiency, noise, and reliability. As a result, it tends to be more expensive and is usually reserved for applications where the performance and lifespan benefits justify the added cost.

Capacitive vs. Inductive Active Balancing

Active balancing isn’t one-size-fits-all there are multiple ways to transfer energy efficiently between cells. Two of the most common approaches are capacitive and inductive balancing. Both aims to move energy from higher-voltage cells to lower-voltage cells, but they do it using different principles and components.

Capacitive Balancing

Capacitive balancing uses capacitors as temporary energy storage to shuttle charge between cells. Here’s how it works in simple terms:

When a high-voltage cell reaches a threshold, the BMS connects it to a capacitor.

The capacitor charges from the high-voltage cell, storing a small amount of energy.

The capacitor is then connected to a lower-voltage cell, discharging its energy into that cell.

This process repeats in cycles until the cells are more balanced.

Pros:

Relatively simple and compact circuitry.

Can handle small to moderate imbalances efficiently.

Works well in medium-capacity packs where high power transfer isn’t needed.

Cons:

Slower for large packs or big imbalances.

Energy transfer is limited by capacitor size and voltage differences.

Efficiency drops if many transfers are needed or if the pack is very large.

Inductive Balancing

Inductive balancing uses inductors to transfer energy more continuously and efficiently. Essentially, it’s like creating a mini-DC-DC converter between cells:

Current is temporarily stored in an inductor from a high-voltage cell.

The magnetic energy in the inductor is then released into a lower-voltage cell.

This process can happen rapidly and repeatedly under precise BMS control.

Pros:

Higher energy transfer rates good for large packs or big imbalances.

More efficient than capacitive methods for high-power systems.

Can operate continuously during both charging and discharging.

Cons:

More complex circuitry and control logic.

Slightly larger footprint and cost due to inductors and switching components.

Requires careful design to avoid noise or energy losses.

Takeaway for readers:

Capacitive balancing is simple and works fine for small or mid-sized packs.

Inductive balancing is more efficient and faster, making it ideal for EVs, energy storage systems, or high-performance packs but it comes at a higher cost and complexity.

When Should Balancing Occur: Charge vs. Discharge?

Balancing is most effective when applied strategically, because cells behave differently depending on whether the pack is charging, discharging, or idle. Understanding when and why balancing occurs is essential for both DIY systems and professional BMS design.

1. Balancing During Charging

Why it’s common:

Charging is the phase where cells reach their upper voltage limits, so differences in cell capacity or internal resistance become most pronounced.

A weak cell may reach full charge before the others, creating an imbalance that limits total usable capacity.

How it works:

The BMS monitors each cell’s voltage and state-of-charge.

Once a cell hits the target voltage threshold, the BMS begins bleeding off excess energy (passive) or redistributing it (active) to slower-charging cells.

Charging-phase balancing is most efficient for preventing overvoltage in stronger cells and maximizing usable capacity of the pack.

Key point: Most commercial systems prioritize balancing near the top of charge, because this is when voltage differences have the greatest impact on safety and capacity.

2. Balancing During Discharging

Why it’s less common:

During discharge, cells deplete energy at slightly different rates, but the voltage differences are usually smaller than during charge.

Imbalance during discharge rarely threatens overvoltage, but under-voltage in a weak cell can prematurely limit usable capacity.

When it’s useful:

Active balancing can transfer energy from higher-voltage cells to weaker cells, effectively extending usable capacity during heavy loads.

This is especially relevant in high-performance packs or long-duration applications where energy efficiency matters.

Limitations:

Passive balancing during discharge is generally inefficient it wastes energy and generates heat unnecessarily.

Active discharge balancing adds complexity and cost, so it’s typically only found in sophisticated systems.

3. Best Practice / Hybrid Approach

Primary balancing: Charge phase ensures all cells reach full SOC safely.

Secondary balancing: Discharge phase optional, usually with active methods for high-capacity or high-performance packs.

Some advanced BMS implement continuous balancing (micro-adjustments during both charge and discharge) to maintain optimal SOC and reduce long-term degradation.

Key Takeaways:

Balancing should always occur during charging, particularly near full charge, to protect cells and maximize capacity.

Discharge balancing is optional but can improve efficiency in large or high-power systems.

The method (passive vs. active) and timing are interdependent active methods allow more flexibility during both charge and discharge, whereas passive is mostly limited to the charging phase.

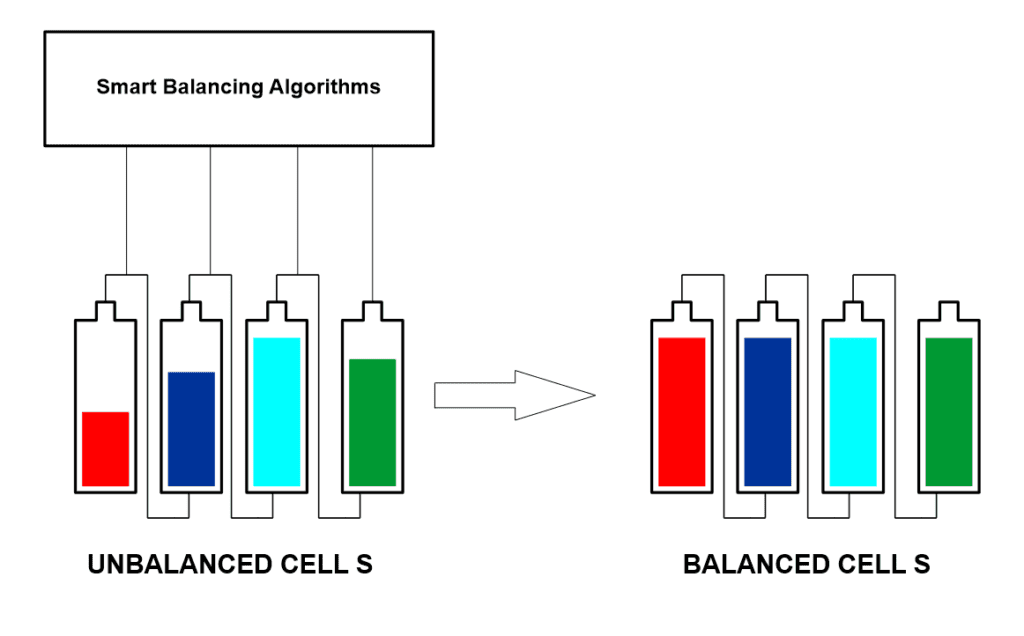

Smart Balancing Algorithms

Traditional battery balancing whether passive or active performs a straightforward function: it equalizes cell voltages to prevent individual cells from exceeding safe limits. While effective at maintaining basic pack health, this approach treats all cells uniformly and does not account for the dynamic behavior of cells during real-world operation.

Smart balancing algorithms, on the other hand, introduce intelligence and adaptability into the process. Instead of simply redistributing or dissipating energy whenever voltage differences appear, these algorithms analyze multiple parameters in real time including cell voltage, state-of-charge (SOC), temperature, internal resistance, and even historical degradation trends to make informed decisions about when, how, and which cells to balance.

Goals of Smart Balancing Algorithms

1. Maximize Cycle Life

By continuously monitoring each cell and avoiding chronic overcharge or deep discharge, smart algorithms reduce stress on the weakest cells, extending the overall lifespan of the pack.

Balancing is no longer reactive; it anticipates cell behavior based on trends and adapts dynamically.

2. Optimize Charging Efficiency

Intelligent redistribution ensures that weaker cells receive energy at the right time, while stronger cells are not overcharged or wasted.

This minimizes energy loss, reduces heat generation, and improves overall pack efficiency compared to simple passive balancing.

Prevent Overvoltage and Undervoltage in Individual Cells

Smart algorithms prioritize vulnerable cells that are approaching voltage thresholds, selectively transferring energy or modulating current to maintain all cells within safe operating limits.

This proactive approach significantly reduces the risk of premature cell degradation or triggering protective cutoffs during high-demand operation.

Key Distinction: Unlike conventional balancing, which often applies energy redistribution uniformly or at fixed thresholds, smart balancing algorithms operate continuously, intelligently, and contextually, making real-time trade-offs that optimize both safety and performance.

How Smart Balancing Algorithms Work

Smart balancing algorithms transform simple voltage equalization into an intelligent, real-time optimization process. They continuously monitor and evaluate each cell, making precise decisions to maximize pack efficiency, lifespan, and safety. The process can be broken down into five key steps:

Step 1: Data Acquisition

The foundation of any smart balancing algorithm is accurate and high-resolution cell data. Each cell in the pack is continuously monitored using dedicated sensors:

Voltage Measurement:

High-precision voltage sensors track each cell’s terminal voltage with millivolt-level resolution, ensuring even small deviations are detected.

Current Measurement:

Current sensors measure both charge and discharge currents, allowing the algorithm to understand energy flow and calculate SOC in real time.

Temperature Monitoring:

Temperature sensors per cell or per module detect thermal gradients, which are critical since temperature affects reaction kinetics, internal resistance, and voltage drift.

Optional Data Enhancements:

SOC Estimation:

Using voltage, current, and coulomb counting methods, the algorithm estimates the state-of-charge of each cell.

SOH Estimation:

Advanced systems track capacity fade and internal resistance over time, enabling predictive adjustments to prevent weak cells from being overstressed.

Outcome:Accurate, continuous data forms the basis for all subsequent analysis and decision-making, ensuring the algorithm can respond proactively rather than reactively.

Step 2: Cell Analysis

Once the data is acquired, the algorithm evaluates the relative state of each cell:

Identifying Weak vs. Strong Cells: Cells that charge faster, discharge sooner, or have lower capacity are flagged as weaker, while cells with higher capacity or slower charge/discharge rates are stronger.

Calculating Imbalance Percentage: The algorithm computes the difference in SOC or voltage between the strongest and weakest cells. This is often expressed as a delta voltage (ΔV) or percentage of SOC difference, e.g.,

This analysis identifies priority cells for balancing and helps the algorithm plan energy redistribution efficiently.

Outcome: The algorithm now has a clear map of which cells need energy adjustment and how severe the imbalance is

Step 3: Decision Logic

With cell imbalances quantified, the algorithm applies decision rules to determine when and how to balance:

When to Start Balancing:

Balancing is usually triggered when ΔV or SOC differences exceed a predefined threshold (e.g., 0.01–0.05 V).

How Much Current to Divert per Cell:

Based on cell capacity, voltage difference, and pack conditions, the algorithm calculates the optimal balancing current for each cell.

Prioritization:

Cells with the largest voltage or SOC deviation are addressed first. In complex packs, the algorithm may also consider thermal limits or cumulative charge cycles to prevent overloading weaker cells.

Outcome: The system decides a precise, prioritized plan of action, ensuring energy is redistributed efficiently and safely.

Step 4: Energy Redistribution (Active Balancing)

In active balancing systems, energy is moved from higher-voltage cells to lower-voltage cells rather than being dissipated as heat:

Mechanism: Energy is transferred using capacitive charge pumps, inductive converters, or switched DC-DC circuits.

Dynamic Adjustment:

The algorithm continuously adjusts the magnitude and duration of energy transfer based on real-time voltage and SOC readings.

Passive vs. Active Flow: Passive systems simply bleed excess energy as heat, which wastes energy and increases thermal load. Active systems reuse energy, improving efficiency and minimizing temperature rise.

Outcome: The weakest cells are brought up to voltage parity without wasting energy, improving overall pack capacity and efficiency.

Step 5: Iteration & Optimization

Since Balancing is an iterative process:

The algorithm continuously monitors all cells and recalculates voltage/ SOC differences after each adjustment.

Adjustments continue until all cells are within a predefined safe voltage tolerance (e.g., ΔV < 0.01 V).

Example: If Cell A = 4.15 V and Cell B = 4.05 V, the algorithm may divert 100 mA from A to B until the difference drops below 0.01 V.

Outcome: Cells remain synchronized in real time, preventing overvoltage, reducing stress on weaker cells, and maximizing cycle life.

Common Algorithms Used in Smart BMS

Smart balancing algorithms have evolved significantly, ranging from simple threshold-based methods to sophisticated predictive models that leverage historical data and AI. Each approach has its own trade-offs in terms of accuracy, efficiency, and complexity, and the choice of algorithm depends on the pack size, application, and performance requirements.

1.Threshold-based Balancing

The simplest approach, is the threshold-based balancing, operates by correcting a cell whenever its voltage deviates beyond a predefined limit relative to the pack average. This method is straightforward to implement, requiring minimal computation, and is often used in small or cost-sensitive packs. While effective for preventing large voltage deviations, it does not account for differences in state-of-charge (SOC), temperature effects, or long-term degradation, and can result in unnecessary energy loss in larger packs.

2.SOC-based Algorithms

A more precise approach uses SOC-based algorithms, which estimate each cell’s true energy content rather than relying solely on voltage measurements. SOC estimation typically combines voltage, current integration, and temperature correction. By focusing on actual energy differences, these algorithms reduce unnecessary balancing actions and improve usable pack capacity. However, SOC-based methods require more sensors and computational resources, and inaccuracies can arise from sensor drift or cumulative integration errors.

3.Predictive Balancing Algorithms

At the forefront of modern BMS design are predictive balancing algorithms, which leverage machine learning or advanced modeling to anticipate cell imbalances before they occur. By analyzing historical data on voltage, SOC, temperature, and current, the algorithm can forecast how cells will drift in future cycles and take corrective action preemptively. This proactive approach minimizes stress on vulnerable cells, extends overall pack lifespan, and maximizes efficiency. The trade-off is greater complexity, requiring substantial data collection, model training, and computational capability.

4.Weighted Balancing Algorithms

weighted balancing algorithms are used in large, complex packs where not all cells are equally critical. These algorithms assign a priority weight to each cell based on its deviation from the pack average, temperature, cycle count, or location within the pack. Cells with higher weights(imbalanced) are addressed first, ensuring that balancing efforts are focused where they matter most. Weighted algorithms optimize efficiency and safety in multi-cell systems but require detailed modeling of the pack architecture and increased computational resources.

Altogether, these approaches illustrate the evolution of battery management from static, reactive balancing to dynamic, intelligent, and predictive control. Modern BMS algorithms combine real-time monitoring, prioritization, and predictive analysis to maximize cycle life, improve charging efficiency, and safeguard individual cells, enabling lithium battery packs to perform safely and reliably under demanding real-world conditions.

Benefits of Smart Balancing

The practical impact of smart balancing algorithms goes far beyond maintaining voltage uniformity. By continuously monitoring each cell and making intelligent adjustments, these systems significantly extend the overall lifespan of a battery pack. Cells are protected from chronic overcharging or deep discharging, which are the primary drivers of premature degradation. Over time, this translates to more cycles, more reliable performance, and lower long-term replacement costs.

In addition to longevity, smart balancing increases the usable capacity of the pack. Because weaker cells no longer limit the overall energy delivery, the system can safely draw closer to the total nominal capacity of the pack. This is particularly valuable in high-demand applications such as electric vehicles, solar storage, or off-grid systems, where every watt-hour counts.

Safety is another critical advantage. Smart algorithms proactively manage voltage and SOC disparities, reducing the risk of overvoltage, undervoltage, and thermal stress that could lead to catastrophic cell failure. By addressing potential issues before they escalate, the BMS provides a layer of protection that passive or simple balancing methods cannot match.

Finally, energy efficiency is optimized. Active redistribution of energy prevents waste, minimizes heat generation, and ensures that energy is used where it is most needed. For solar storage systems, electric vehicles, or off-grid applications, this translates to more effective charging, longer runtime, and improved overall system performance.

smart balancing transforms a battery pack from a simple energy reservoir into an intelligently managed system, maximizing both performance and reliability under real-world operating conditions.

Difference Between Conventional and Smart Balancing

Conventional balancing whether passive or active operates in a mostly reactive and uniform way. Passive balancing simply dissipates excess energy as heat whenever a cell exceeds a voltage threshold, while active balancing redistributes energy between cells to equalize voltages. Both methods rely primarily on instantaneous voltage readings, and neither considers broader operational metrics. Their main limitation is that they treat all cells the same, without anticipating how the pack will behave over time.

Smart balancing, on the other hand, is an intelligent layer built on top of active balancing hardware. While it often still uses active energy transfer to redistribute charge efficiently, it adds context, prioritization, and predictive logic:

1.Multiple Metrics:

Smart algorithms incorporate cell voltage, SOC, SOH, temperature, current, and even historical degradation patterns.

2.Decision Logic:

Balancing is not triggered by a simple threshold but by calculated deviations and priorities. Weaker or more critical cells are corrected first.

3.Predictive Control:

Some systems anticipate future imbalance trends, applying corrective measures proactively rather than waiting for voltage differences to appear.

4.Continuous Optimization:

Balancing occurs iteratively and dynamically, rather than as a one-time correction at the top of charge.

In short, smart balancing transforms active balancing from a reactive hardware operation into a real-time, intelligent management system. It uses more sensors, more data, and advanced logic to maximize safety, efficiency, and pack life something conventional methods cannot achieve.

Conclusion

Smart balancing algorithms are the cornerstone of modern battery management, transforming simple voltage equalization into a dynamic, intelligent system that safeguards each cell while maximizing efficiency and longevity. By continuously monitoring voltages, state-of-charge, temperature, and cell health, these algorithms ensure that packs operate safely, deliver their full capacity, and withstand thousands of cycles without premature degradation.

For beginners and DIY enthusiasts, understanding the principles of balancing starting with simple circuits and gradually incorporating more sophisticated techniques can provide valuable insights into battery behavior and system design. Even modest experimentation can teach critical lessons about energy distribution, efficiency, and safety, laying the groundwork for more advanced projects.

To continue exploring, check out our other BMS guides, download DIY resources, and subscribe to stay updated on advanced techniques in battery management.

Hi, i am Engr. Ubokobong a solar specialist and lithium battery systems engineer, with over five years of practical experience designing, assembling, and analyzing lithium battery packs for solar and energy storage applications, and installation. His interests center on cell architecture, BMS behavior, system reliability, of lithium batteries in off-grid and high-demand environments.