Introduction

I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve walked onto a job site and seen an installer hesitate over a high voltage vs low voltage inverter decision. Just last month, I consulted on a residential solar project where the homeowner had purchased a 12V inverter for an 8 kW system because “lower voltage is safer.” The DC cable runs alone would have cost more than switching to a properly designed high-voltage setup, and that was before we even started talking about efficiency losses.

The confusion is understandable. When comparing inverters, you’ll see systems operating anywhere from 12V to 600V or higher, all claiming to be the “best” option. Marketing materials highlight efficiency percentages and safety certifications without explaining what those numbers actually mean for real installations. Ask three different installers which inverter voltage to use, and you’ll often get three different answers.

Here’s what actually matters: the high voltage vs low voltage inverter choice fundamentally changes how a system behaves, how much current it carries, how much copper it requires, how efficient it runs, how much heat it generates, and which failure modes are most likely to show up over time. This isn’t about one approach being universally better; it’s about matching the voltage architecture to the real demands of the system.

In this guide, I’ll walk through the technical realities behind high voltage and low voltage inverter systems. We’ll cover DC bus voltage and why it matters, real-world efficiency figures (not datasheet marketing), counterintuitive safety considerations, true installation costs including often-overlooked wiring losses, and a practical framework for choosing the right system for your application.

This is written from the perspective of someone who has designed battery systems, troubleshot failed installations, and seen firsthand what works in the field versus what only looks good on paper. It’s for solar installers making design decisions, battery builders integrating energy storage, electrical engineers specifying components, and technically curious system owners who want to understand what they’re actually buying.

If you’re looking for a simple “just buy this inverter” recommendation, you won’t find it here. But if you want a clear understanding of the trade-offs that drive the high voltage vs low voltage inverter decision, and how to choose correctly for your situation, keep reading.

TL;DR

Low Voltage (12V-48V):

- Best for: Systems under 3kW, off-grid, RVs/boats, DIY installation

- Pros: Simple, cheaper upfront, safer to handle, widely available components

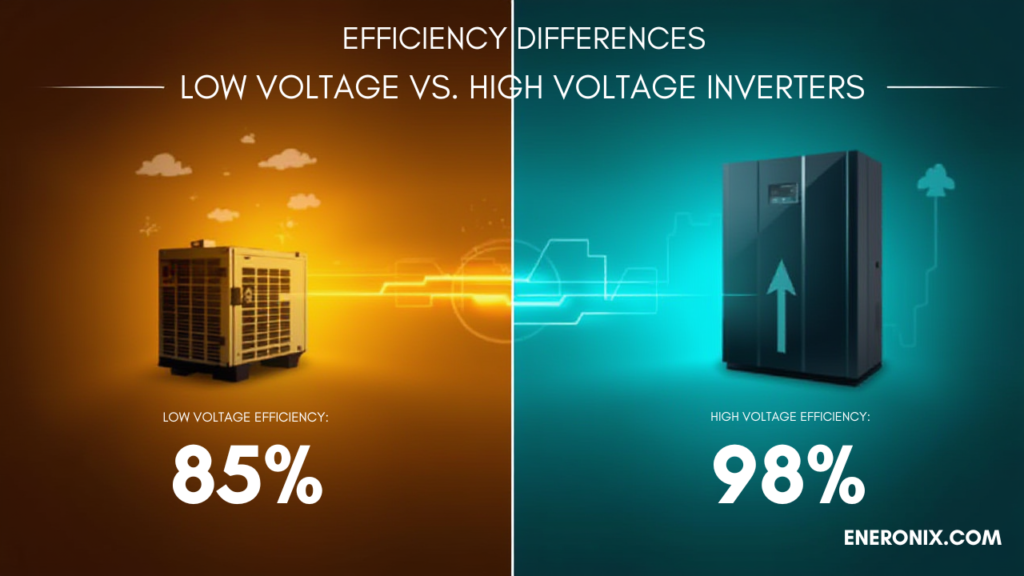

- Cons: High current = thick expensive cables, efficiency losses (90-95%), voltage drop over distance

- Cost: Lower components, higher wiring costs, 6-8% energy losses annually

High Voltage (150-600V):

- Best for: Systems 5kW+, grid-tied solar, professional installation, long cable runs

- Pros: Better efficiency (96-98%), thin cables, scales easily, lower fire risk

- Cons: Requires certified installers, higher upfront cost, arc flash risk

- Cost: Higher components, lower wiring costs, 3-4% energy losses annually

The 3-5kW Gray Zone:

- 48V works if: DIY capable, tight budget, short cables (under 3m), no expansion plans

- High voltage works if: Professional install, long runs (5m+), future expansion likely

Bottom Line: Match voltage to your power level and installation situation. Under 3kW? Go low voltage. Over 5kW? Go high voltage. Both work when installed properly—quality matters more than voltage choice.

Voltage Definitions & What We’re Comparing

Before we can compare anything meaningfully, we need to establish what we’re talking about. The terms “high voltage” and “low voltage” get thrown around inconsistently in the solar industry, and that creates confusion.

High Voltage vs Low Voltage inverter

When I refer to low voltage (LV) inverter systems, I’m talking about inverters that operate with DC input voltages of 12V, 24V, 48V, or 96V. These are battery-based systems where the inverter’s DC input voltage matches the battery bank voltage. You’ll find these in off-grid installations, backup power systems, RVs, boats, and smaller residential setups. The 48V category dominates residential applications because it offers better efficiency than 12V or 24V while still remaining relatively safe to work with.

High voltage (HV) inverter systems in residential and small commercial contexts typically operate at 150V to 600V DC input. These are primarily grid-tied string inverters or high-voltage battery-coupled systems that can handle the higher voltages coming from solar panel strings or high-voltage battery assemblies.

Here’s where terminology gets messy: electrical codes define “low voltage” as anything under 1000V AC or 1500V DC from a regulatory standpoint. But in practical solar system design, when we say “high voltage inverter,” we mean something fundamentally different in operation from a 48V battery inverter, even though both might fall under the same code classification. What matters for this discussion is the operational voltage architecture, not the regulatory label.

Why Voltage Matters

The difference between low and high voltage systems isn’t just a number, it fundamentally changes how your system behaves. The reason comes down to basic physics: Power = Voltage × Current.

For the same power output, lower voltage means higher current. A 5kW load at 48V pulls about 104A from the battery. Drop that to 24V and you’re pulling 208A. At 12V, you’re at 417A. Those aren’t trivial differences.

High current creates real problems:

- Thicker cables required (expensive and difficult to work with)

- Larger terminals and connectors needed

- More voltage drop over distance

- More resistive heating (wasted energy as heat)

- Heavier gauge breakers and switches

I’ve seen 12V systems where the cable between the battery and inverter weighs more than the inverter itself. The 70mm² cable required for high-current DC runs gets stiff and unmanageable, and every connection point becomes a potential failure spot under thermal cycling.

High voltage systems flip this equation. That same 5kW load at 400V pulls only 12.5A. Suddenly you’re working with manageable cable sizes, smaller terminals, and minimal voltage drop even over longer runs. The current is low enough that cable sizing becomes almost trivial compared to low voltage installations.

System Architecture Differences

Low voltage systems operate on a straightforward principle, your battery voltage defines your system voltage. A 48V battery bank feeds a 48V inverter. Want more capacity? Add batteries in parallel. Want more power? Add another inverter or upgrade to higher capacity. The architecture is simple and modular, which is exactly why it’s popular for DIY installations and off-grid systems where simplicity is preferred.

Also check out: The Lithium Battery Architecture Handbook: A Systems Guide to Cells, BMS, and Internal Engineering

High voltage systems are more complex architecturally. You can’t just parallel batteries the same way, you need to build and maintain a proper voltage stack. For solar integration, high voltage typically means string inverters where you wire panels in series to reach 300-600V and feed that directly into the inverter’s MPPT input. This is why grid-tied solar installations almost universally use high-voltage string inverters it’s the most direct path from panel to grid.

Now that we’ve established what distinguishes these systems architecturally, let’s look at where that voltage difference shows up in real performance: efficiency.

Efficiency

When people compare inverters, efficiency percentages get thrown around like they’re the only number that matters. You’ll see spec sheets claiming 97% here, 98% there, and marketing materials suggesting that extra percentage point will transform your system. In practice, efficiency is important, but the real story is more nuanced than a single number on a datasheet.

Let’s start with what you’ll actually see in the field. High voltage inverters typically deliver 96-98% conversion efficiency at their rated operating point. Modern units with good thermal management and quality components can hit 97.5-98% pretty consistently.

Low voltage inverters generally land in the 90-95% range, though well-designed 48V units from quality manufacturers can reach 95-97%. The 12V and 24V systems tend to sit at the lower end of that range I regularly see 12V inverters running at 88-92% efficiency under real-world conditions.

For battery-coupled systems, you also need to consider round-trip efficiency the energy lost going into and out of storage. High voltage battery systems typically achieve 93-96% round-trip efficiency. Low voltage systems come in at 90-93%. That might not sound like much, but over thousands of charge-discharge cycles, it adds up.

Why High Voltage Is More Efficient

The efficiency advantage of high voltage systems comes down to current flow and resistive losses. Every conductor cables, busbars, terminals, even PCB traces has resistance. When current flows through resistance, you lose energy as heat. The loss follows the I²R formula: where power loss equals current squared times resistance.

This is why voltage matters so much. At 48V, your 5kW inverter is pulling 104A on the DC side. At 400V, that same 5kW pulls 12.5A. Square those currents and you’ll see why high voltage systems bleed less energy in the wiring and connections. The 48V system is losing energy at a rate proportional to 104² = 10,816. The 400V system? 12.5² = 156. That’s a 69x difference in resistive heating for the same power transfer.

Even with perfectly sized cables, you can't escape physics. Lower current means lower I²R losses, period.

The other efficiency factor is conversion stages. A 48V battery-based inverter typically boosts the DC voltage internally before inversion you’re going from 48V to maybe 350-400V, then inverting to AC. Each conversion step costs you 1-3% efficiency. A high voltage system feeding from a 400V battery or solar string skips that boost stage entirely. Fewer conversions, fewer losses.

Real-World Efficiency Factors People Miss

Spec sheet efficiency numbers are measured under ideal conditions: 25°C ambient temperature, rated load, steady-state operation. Real installations don’t work like that.

1. Temperature kills efficiency

Inverters work best at 25-35°C. Get above 40°C and you’ll see efficiency drop by 2-4% depending on the design. I’ve seen inverters installed in hot utility rooms or poorly ventilated enclosures running 5-7% below their rated efficiency just from heat. This affects both low and high voltage systems, but low voltage systems generate more heat from the higher currents, which compounds the problem.

2. Partial load efficiency matters more than peak

Your inverter rarely runs at 100% rated capacity. Most of the time it’s cycling between 20-60% load as appliances turn on and off. Low voltage inverters often show a bigger efficiency drop at partial loads a 48V inverter rated at 95% at full load might only deliver 88-90% at 25% load. High voltage units tend to maintain flatter efficiency curves across the load range.

3. Cable losses are the hidden killer in LV systems.

Here’s what catches people: they’ll buy a 95% efficient 48V inverter and think they’re getting 95% system efficiency. Then they run 3 meters of slightly undersized cable and lose another 3-4% in the DC wiring alone. I’ve tested 48V systems where the inverter was performing to spec, but total DC-side losses (cables, breakers, busbars, battery terminals) were eating 6-8% before the power even reached the inverter.

With high voltage systems, cable losses become almost negligible. Even with modest cable sizing, voltage drop is minimal at low currents.

What This Looks Like in Practice

Let me give you a concrete example. A 6kW solar system in a residential installation, running about 25kWh per day through the inverter.

Low voltage scenario (48V):

Inverter efficiency 93%, DC cable and connection losses 4%, total system efficiency around 89%. You’re losing about 2.75kWh per day to conversion and wiring losses. Over a year, that’s roughly 1,000kWh gone to heat.

High voltage scenario (400V):

Inverter efficiency 97%, DC cable losses under 1%, total system efficiency around 96%. Daily losses drop to about 1kWh. Annual losses: ~365kWh.

The difference is 635kWh per year. At typical electricity costs, that’s real money. Over a 10-year system life, you’re talking about 6,350kWh of energy that either powers your home or heats up your wiring.

The Installation Quality Reality

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: a well-installed low voltage system will outperform a poorly installed high voltage system every time.

I’ve seen high voltage installations where the installer used undersized DC breakers that created hot spots, or made poor crimps on MC4 connectors that introduced resistance. I’ve seen 48V systems with meticulous wiring, proper torque on every terminal, and appropriately oversized cables that delivered better real-world performance than their efficiency rating suggested.

The spec sheet gives you the ceiling. Installation quality determines how close you get to it.

When LV Efficiency Is Good Enough

This is where I push back on the “always choose high voltage for efficiency” narrative. If you’re running a 2kW off-grid cabin system and your loads are modest, the difference between 92% and 97% efficiency might be 100-150kWh per year. That’s marginal. The reliability and simplicity of a well-designed 48V system can matter more than chasing efficiency percentages.

But scale that same efficiency difference to a 10kW system running heavy daily loads, and now you’re looking at 1,500-2,000kWh annual losses in the LV system versus the HV alternative. That efficiency gap starts paying for the higher upfront cost of high voltage components.

The efficiency advantage of high voltage systems is real and measurable. Lower current flow means lower resistive losses, fewer conversion stages mean less energy lost in transformation, and better partial-load performance means consistent efficiency across varying demand. But efficiency doesn’t exist in isolation—it has to be weighed against installation complexity, cost, and the specific requirements of your application.

1. Safety

Most people assume lower voltage is automatically safer. It’s partially true, but the reality is more complicated.

12V to 48V systems are safer to handle during installation. You can touch live 48V terminals without getting shocked the voltage isn’t high enough to overcome skin resistance under normal conditions. This makes them more forgiving for DIY installers and reduces PPE requirements.

The risk at low voltage systems isn't shock. It's fire.

High current creates heat. A poor crimp, loose terminal, or undersized cable under 100+ amps generates serious heat at the connection point. I’ve seen melted battery terminals, burned busbars, and charred cable insulation in 48V systems—all from connections that looked fine during installation but failed under thermal cycling.

The problem compounds over time. Connections oxidize, resistance increases slightly, heat generation goes up, oxidation accelerates. What starts as a warm terminal becomes a failure point.

The High Voltage Paradox

Here’s what catches people off guard: high voltage systems, properly installed, have lower fire risk than low voltage systems.

The reason is current. At 400V, you’re running 10-15A instead of 100-150A. Thinner cables, smaller terminals, less heat generation at every connection point. The system runs cooler, connections don’t thermally stress, and there’s less energy available to start a fire if something does fail.

But—and this is critical—high voltage brings arc flash risk. If you create an air gap while breaking a DC circuit under load, you can sustain an arc. DC arcs don’t self-extinguish like AC arcs do. I’ve seen arc flash incidents that melted tools and burned hands. This is why high voltage work requires proper isolation procedures and PPE.

The shock risk is also real above 50V. 400V DC can definitely hurt you. But in practice, properly designed high voltage systems have better isolation, require rapid shutdown features, and force installers to follow shutdown procedures. Low voltage systems get treated casually because “it’s only 48V,” and that’s where mistakes happen.

What Actually Causes Safety Failures

In low voltage systems:

Poor crimps, undersized cables, loose terminals, inadequate torque on connections. All result in overheating and potential fire. The most common failure I see is using automotive-style crimp connectors on high-current DC circuits—they’re not designed for continuous 100A+ and they fail.

In high voltage systems:

Improper shutdown procedures, inadequate isolation during maintenance, DIY attempts by unqualified people. Arc flash from breaking live circuits. The failures are less frequent but more dramatic when they happen.

Required Safety Features

Both systems need proper protection:

- Overcurrent protection: Breakers or fuses sized correctly for cable ampacity

- Ground fault detection: Detects current leakage to ground

- Rapid shutdown: Required on high voltage solar systems, allows quick de-energization

- Arc fault protection: Increasingly required, detects dangerous arcing conditions

High voltage systems have stricter requirements. Rapid shutdown is mandatory in most jurisdictions for systems above 80V. Arc fault protection is becoming standard. These add cost but meaningfully reduce risk.

Installation Requirements

Low voltage (12-48V): Can often be owner-installed depending on local codes. Requires understanding of DC electrical systems but doesn’t typically require licensed electrician certification.

High voltage (150V+): Requires certified installers in most jurisdictions. Proper training on isolation procedures, PPE requirements, and code compliance. This adds labor cost but reduces installation risk.

The trade-off: low voltage is cheaper to install if you DIY, but you own the risk. High voltage forces professional installation, which costs more but transfers liability and ensures code compliance.

My Honest Assessment

Low voltage is safer to work on during installation. You’re less likely to get shocked, and mistakes are more forgiving in the moment.

High voltage, properly installed, is safer in operation. Lower current means less thermal stress, reduced fire risk, and better engineered safety systems.

The middle ground is 48V systems. Still relatively safe to handle, but high enough current that installation quality matters significantly. If you’re going to DIY, 48V is the ceiling I’d recommend without proper training.

What matters most isn’t the voltage, it’s whether the installation is done correctly. A sloppy 48V system with poor connections is more dangerous than a well-executed 400V system with proper isolation and protection.

Installation Complexity & True System Costs

The sticker price on an inverter doesn’t tell you what the system actually costs. Installation labor and balance-of-system components, especially cabling, often exceed the inverter cost itself.

Upfront Component Costs

High voltage inverters cost 15-25% more than equivalent low voltage units. A 5kW high voltage inverter might run $1,200-1,800 versus $900-1,400 for a 48V inverter. High voltage batteries also carry a premium, more complex BMS, higher voltage cell configurations, stricter safety requirements.

Low voltage inverters have lower entry costs. The technology is mature, competition is high, and you’re buying into an established ecosystem. 48V lithium batteries are commodity products at this point.

On component costs alone, low voltage looks cheaper. But components aren’t where the real money goes.

Where Low Voltage Gets Expensive

1. Cable sizing

Cable sizing follows current, not power. This is where low voltage economics fall apart.

Example: 6kW system, 5 meter run from battery to inverter

At 48V: 125A continuous current. You need 50mm² cable minimum to keep voltage drop under 2%. That’s thick, expensive cable—$8-12 per meter for quality copper. For a 5 meter run (10 meters total for positive and negative), you’re at $80-120 just in cable.

At 400V: 15A continuous current. 6mm² cable is adequate. Cost: $2-3 per meter. Same 5 meter run costs $20-30.

The cable cost difference alone: $50-90 for this single run. Now multiply that across battery interconnects, solar DC runs, and any other high-current paths in the system.

Terminals, lugs, and breakers also scale with current. A 125A DC breaker costs 3-4x what a 20A breaker costs. Crimp lugs for 50mm² cable are $5-8 each versus $0.50-1 for 6mm² lugs. It adds up fast.

I’ve seen residential 48V systems where the DC-side cabling and hardware cost more than the inverter. The 400V equivalent used a fraction of the copper and simpler hardware.

2. Installation Labor

High voltage systems are faster to wire. Thinner cables, fewer terminations, less physical wrestling with heavy conductors. But they require certified installers, and certified labor costs $80-150/hour depending on location.

Low voltage systems take longer to wire properly. More parallel battery connections, heavier gauge cables that are harder to route and terminate, more connection points to torque correctly. But in jurisdictions that allow owner installation, you can DIY and save labor costs entirely.

The trade-off: if you’re paying for professional installation anyway, high voltage is often cheaper total install cost despite higher hourly rates. The job goes faster and uses less material. If you’re capable of DIY work, low voltage lets you trade your time for money savings.

Also read: Why Most Solar-Battery Systems Fail Before Year 2

One caveat: DIY 48V installations often have quality issues I see later. Undertorqued terminals, inadequate cable support, poor routing that causes voltage drop. You save money upfront but risk problems later.

3. Long Cable Runs

Voltage drop is proportional to current and distance. For low voltage systems, anything beyond 3 meters starts requiring serious cable oversizing.

At 48V, a 10 meter run to a battery bank needs 70-95mm² cable to maintain acceptable voltage drop under load. That’s cable you can barely bend, terminals that require hydraulic crimpers, and installation that’s genuinely difficult.

At 400V, the same 10 meter run works fine with 10-16mm² cable. Easy to route, simple to terminate, minimal voltage drop.

If your battery location is more than 5 meters from your inverter, low voltage becomes painful. High voltage doesn’t care, I’ve done 15 meter runs with standard cable sizing and negligible loss.

4. Scalability & Future Expansion

Low voltage systems scale by adding parallel batteries and potentially parallel inverters. Each addition means more wiring, more connection points, more complexity. Going from 10kWh to 20kWh battery capacity means doubling your battery interconnects and potentially upgrading cables if you’ve increased discharge current.

High voltage systems scale more cleanly. Adding battery capacity usually means adding modules to the voltage stack without massive wiring changes. The current stays similar, so existing infrastructure often handles expansion.

In practice: I see people start with a 5kW 48V system, then want to expand to 8-10kW and discover they need to rewire the entire DC side because the original cables won’t handle the higher current. High voltage systems expand without infrastructure overhaul.

5. Total Cost Over 5-10 Years

Initial purchase: Low voltage wins, typically 10-20% cheaper on components.

Installation: Depends on labor situation. Professional install often favors high voltage due to speed. DIY favors low voltage if you’re competent.

Efficiency losses: High voltage saves 500-1,000kWh annually on a typical 6-8kW system. Over 10 years at $0.15/kWh, that’s $750-1,500 in operating savings.

Expansion costs: High voltage is cheaper to scale if you add capacity later.

For small systems (under 3kW) that won’t expand, low voltage makes economic sense. For larger systems (5kW+) or anything with expansion plans, high voltage usually wins on total cost of ownership despite higher upfront cost.

Use Cases & System Sizing

The right voltage isn't about which system is "better", it's about which one fits your specific requirements. Here's how I approach the decision based on system size and application.

1. Small Systems (Under 1.5kW): Low Voltage Territory

12V and 24V systems make sense here. RVs, boats, small cabins, mobile applications, basic backup power for essentials.

Why low voltage wins:

- Component availability is excellent (automotive and marine ecosystem)

- Battery options are cheap and plentiful

- Simple architecture, easy to understand and maintain

- Can often DIY installation

- Power requirements don’t justify high voltage complexity

At this scale, you’re pulling 50-125A at 12V or 25-65A at 24V. Manageable with proper cable sizing over short distances. The efficiency penalty is real but the total energy loss is small, maybe 150-300kWh annually. Not worth the cost and complexity of going high voltage.

Example: Weekend cabin, 800W peak load, 3kWh battery. A 12V system with 300Ah of lithium batteries works perfectly. Simple, reliable, cheap to build.

2. Medium Systems (1.5kW - 5kW): The Decision Zone

This is where 48V low voltage competes with entry-level high voltage, and the choice depends on several factors.

48V makes sense when:

- Budget is tight and you’re doing DIY installation

- Loads are moderate and predictable

- Battery to inverter distance is under 3 meters

- No plans for significant expansion

- You want simplicity and easy troubleshooting

High voltage starts making sense when:

- You’re paying for professional installation anyway

- Cable runs exceed 5 meters

- You have high peak loads (water pumps, power tools, kitchen appliances)

- Future expansion is likely

- System will integrate with solar (grid-tied or high-voltage battery-coupled)

In practice, 48V is the workhorse for residential backup power in the 3-5kW range. It’s proven, reliable, and there’s enormous component selection. But if you’re building new and paying an installer, high voltage often comes out ahead on total cost once you factor in wiring.

Example: Residential backup, 3.5kW inverter, 10kWh battery, powering refrigeration, lights, and some outlets during outages. Both 48V and 250V systems work here. I’d lean 48V if the homeowner wants to understand and maintain it themselves, high voltage if it’s professionally installed and they want maximum efficiency.

3. Large Residential (5kW+): High Voltage Makes Sense

Once you’re above 5kW, high voltage becomes the clear choice for most applications.

The current at 48V becomes problematic. An 8kW inverter pulls 165A+ from the battery. That’s 95mm² cable territory, expensive breakers, and heavy terminals. The wiring cost and complexity often exceeds the inverter cost premium for going high voltage.

High voltage systems at this scale typically run 300-600V, pulling 15-30A for the same power. Cable sizing is straightforward, voltage drop is minimal, and efficiency stays high.

This is also where grid-tied solar dominates, and grid-tied solar is almost exclusively high voltage. String inverters operating at 300-600V are the standard architecture. If you’re doing whole-home solar with battery backup, you’re building a high voltage system.

Example: 8kW solar array, 20kWh battery storage, whole-home backup including HVAC and cooking. High voltage architecture with string inverters or high-voltage battery-coupled system. The efficiency gains, simpler wiring, and ability to handle high loads make low voltage impractical here.

Off-Grid vs Grid-Tied Considerations

Off-grid systems

Off-grid systems are battery-centric. Your inverter runs from batteries, solar charges batteries, and the battery bank is the heart of the system. Both low and high voltage can work depending on scale. Below 5kW, 48V is common. Above that, high voltage battery systems make more sense.

Grid-tied systems

feed solar directly to the grid through the inverter, with batteries as optional backup. These are almost universally high voltage because string inverters are the most efficient architecture for solar-to-grid conversion. You’re not building a grid-tied system with a 48V inverter unless it’s a very small installation.

Hybrid systems

Hybrid systems (grid-tied with battery backup) typically use high voltage architecture with sophisticated inverter/chargers that manage solar, grid, battery, and loads simultaneously. The control logic is complex, but the electrical architecture benefits from high voltage’s efficiency and current handling.

Specific Load Considerations

High inrush loads

(well pumps, air compressors, large motors) require inverters that can handle 2-3x surge capacity. Low voltage inverters often struggle here because the surge current is enormous—a 2kW motor starting at 48V might pull 300-400A momentarily. High voltage handles this more gracefully.

Continuous high power loads

(central HVAC, electric water heaters, large refrigeration) push low voltage systems hard. Running 3-4kW continuously at 48V for hours generates significant heat in all the DC connections. High voltage runs cooler and more efficiently.

Mixed residential loads

with everything from LED lighting to kitchen appliances work fine on either system if sized correctly. This is where installation quality matters more than voltage choice.

What I Actually Recommend

Choose 12V or 24V if you’re under 1.5kW, mobile application, or existing 12V/24V ecosystem (RV, boat).

Choose 48V if you’re 1.5-5kW, DIY installation, moderate loads, short cable runs, want simplicity, and no major expansion plans.

Choose high voltage (150-600V) if you’re over 5kW, professional installation, grid-tied solar, long cable runs, high peak loads, or expect future expansion.

The system size and application tell you which voltage makes sense. Trying to force low voltage into a large installation or high voltage into a tiny system both create unnecessary problems.

Decision Framework

After walking through voltage definitions, efficiency, safety, costs, and use cases, here’s how I actually make the decision when someone asks me which system to build.

Start With Four Questions

1. What's your actual power requirement?

Not what you think you might need someday—what do you need now, plus reasonable near-term growth. A 3kW system with dreams of “maybe expanding later” is a 3kW system. Design for that.

Under 3kW: Low voltage is viable and often preferred. 3-5kW: Either can work, depends on other factors. Over 5kW: High voltage makes sense unless you have specific reasons otherwise.

2. How far is your battery from your inverter?

This matters more than people realize.

Under 2 meters: Low voltage works fine with proper cable sizing. 2-5 meters: Low voltage gets expensive on cables, but manageable. Over 5 meters: High voltage strongly recommended. The cable cost and voltage drop in low voltage systems becomes painful.

3. Who's installing it?

If you’re DIY and competent with electrical work: 48V gives you simplicity and cost savings. Just don’t cheap out on cables and connections.

If you’re hiring professional installation: High voltage often costs less total despite higher hourly rates because installation is faster and materials are cheaper.

If you’re DIY but not experienced with DC electrical: Stick with very small 12V systems or hire a professional. 48V systems at 100+ amps are unforgiving of mistakes.

4. What's your budget reality?

Tight upfront budget, willing to accept efficiency losses: Low voltage saves money now.

Optimizing for 5-10 year total cost: High voltage usually wins through efficiency savings and lower wiring costs.

Common Mistakes I See

Undersizing cables to save money on low voltage systems. This destroys your efficiency gains and creates fire risk. If you can’t afford proper cables, you can’t afford low voltage at that power level.

Choosing high voltage for tiny systems. A 1.5kW high voltage system is overkill. You’re paying for complexity you don’t need.

Not planning for expansion. Starting with 48V, then realizing you need 8kW and having to rewire everything. If expansion is remotely likely, build high voltage from the start.

DIY high voltage without training. I’ve seen dangerous installations from people who thought “it’s just like 48V but higher voltage.” It’s not. Arc flash risk and isolation requirements are real. Get proper training or hire someone.

Ignoring installation quality for spec sheet numbers. A 97% efficient inverter with poor connections and undersized wiring might deliver 90% system efficiency. A 94% inverter installed correctly delivers 94%. Quality matters more than specs.

My Practitioner Take

After years of building, troubleshooting, and upgrading systems, here’s what I tell people:

The trend toward high voltage for residential solar is justified. The efficiency gains, cleaner scaling, and lower wiring costs make sense once you’re above 5kW. Grid-tied solar should be high voltage, period.

But low voltage, especially 48V, still has legitimate territory. Small off-grid systems, backup power for modest loads, DIY installations, and anywhere simplicity matters more than peak efficiency. The technology is mature, reliable, and well-supported.

For most residential installations above 5kW with professional installation, high voltage wins on total cost of ownership. For smaller systems or DIY builds under 3kW, low voltage makes more sense.

The middle ground (3-5kW) depends on your specific situation, installation capability, and priorities.

Before You Buy

Whatever you choose, do this:

Calculate your actual power needs. Don’t guess. Measure your loads or use a power monitor for a week. Design for reality, not aspirations.

Measure your cable run distances. Walk the installation with a tape measure. Distance drives costs in low voltage systems.

Get quotes for both systems if you’re in the 3-7kW range. Compare total installed cost, not just component prices. Include proper cable sizing in both quotes.

Consider your 5-year plans. Will you add EV charging? Expand battery capacity? Add more solar? Build the infrastructure now if expansion is likely.

Don’t sacrifice installation quality to save money. The best system is the one installed correctly. Proper cable sizing, correct torque on terminals, appropriate breakers, and good workmanship matter more than voltage choice.

There’s no universally “better” system. There’s only the better fit for your requirements, budget, and capabilities. Match the voltage architecture to your application, install it properly, and both systems will serve you well.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the choice between high-voltage and low-voltage inverters is not about which technology is “better,” but about selecting the architecture that best fits the application. Low-voltage systems prioritize simplicity and accessibility, making them well-suited for small-scale, off-grid, and DIY installations. Their trade-off is high current, which drives up conductor size, hardware costs, thermal stress, and efficiency losses as system power increases.

High-voltage systems, by contrast, trade simplicity for performance and scalability. By operating at lower currents, they enable higher efficiency, longer cable runs, and cleaner expansion at medium to large system sizes. These benefits come with increased design complexity, stricter safety requirements, and higher upfront component costs, which are justified primarily in professionally installed or higher-power systems.

There is no universal winner. The correct decision depends on power level, installation distance, growth plans, installer capability, and long-term objectives. A sound choice is made by evaluating real load requirements, comparing total system costs over 5–10 years, and understanding the implications of each voltage level. Above all, installation quality remains decisive: correct cable sizing, proper torque, suitable protection, and disciplined workmanship will have a greater impact on safety, reliability, and lifespan than voltage level alone.

Hi, i am Engr. Ubokobong a solar specialist and lithium battery systems engineer, with over five years of practical experience designing, assembling, and analyzing lithium battery packs for solar and energy storage applications, and installation. His interests center on cell architecture, BMS behavior, system reliability, of lithium batteries in off-grid and high-demand environments.